The above title is a very good question.

Shown below are three of the seven known Dyottville Glass Works of Philadelphia West Point Class of 1846 commemorative bottles that I have found in my research thus far. There is an example in a collection in Northern California that I currently do not have a photograph of, but confirmed it’s existence by having spoken to it’s owner. He has seen pictures of both mine and the Port Isabel, Texas examples and confirmed that his example is identical in every way. (I would number his as the fourth.)

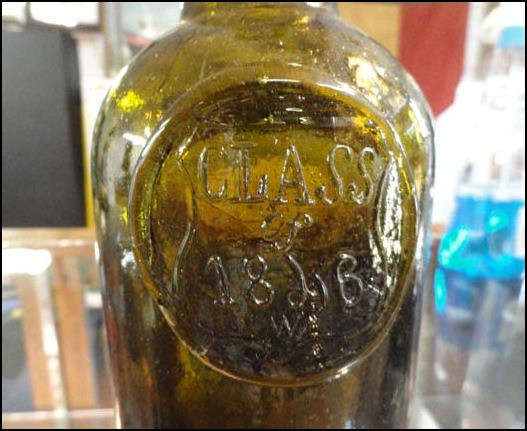

We’ll start by examining the number one example, already documented in the repository of the University of Texas at Brownsville, and is currently on display in an important collection of Mexican American War artifacts and memorabilia in the City of Port Isabel Museum in Port Isabel, Texas.

This example provides a very detailed look at the bottle and a good overall idea of the distinct yellow olive color of the glass. Note below in a detail close up, the Federal Shield is impressed into the seal straight on and does not angle.

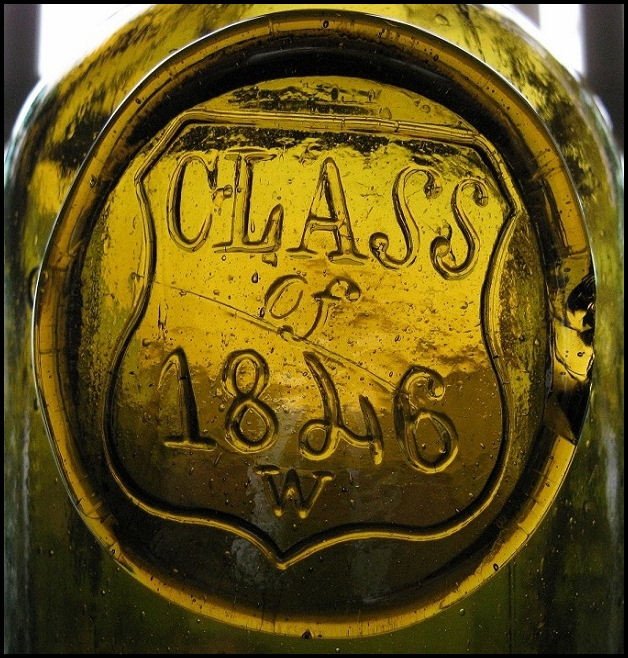

Below is my example, number two. Although the lighting conditions are different, the color is identical. All of the examples I’ve seen are this color and were definitely produced in one lot, from the same batch of glass.

Continuing with my example, note the seal featured below. The Federal Shield was hand impressed into the seal at an angle and is skewed to the right a few degrees. This is the only real difference I have noticed, aside from the height of the bottles measuring between 11-1/4″ to 11-1/2″ due to primitive manufacturing methods in which the bottle was blown into a 2 part mold and the top being hand applied by the maker. The neck length, understandably, could easily vary by a small amount due to each example being literally hand made.

Below is shown the base, featuring the mold embossing of the manufacturer, ‘Dyottville Glass Works Phila’ and in the center is a very prominent iron oxide pontil residue. The iron pontil, or, called in the 1840’s, an “Improved Pontil,” was an easier method than the earlier glass rod pontil method in which a molten ended rod of glass was stuck to the base to hold it while the top was being formed or applied. The iron pontil method was use in 1840 until 1860, after which a “snap case,” or “sabot,” (a cradle type tool) was used to hold the bottle while the top was tooled or applied. This iron pontil proves without a doubt that the manufacturing method is right in line with the 1846 date on the applied seal and that these bottles do indeed date to 1846.

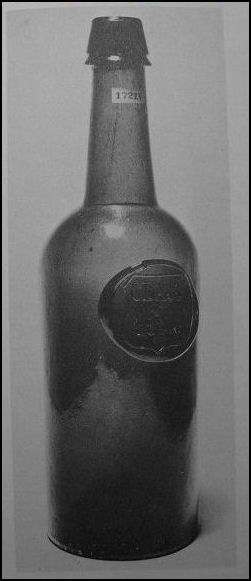

In attempts to document the amount of known examples, I was able to locate a photograph of one in Helen McKearin’s “Bottles, Flasks, and Dr Dyott,” from the late Charles Gardner Collection on page 119, Plate 1, shown below. (Number three example.)

McKearin does not identify the example as West Point, nor did she try. She only attempts to classify the cylindrical whiskey type bottle and manufacturer. What is most interesting is another photograph I found online; an example that sold at Heckler’s Auction some years ago, date unknown. I was referring to this example as a ‘Floater,’ as I cannot locate where it is, or who owns it. This ‘Floater’ example is shown below.

If you examine both examples; despite the older 1941 black and white McKearin photo showing the bottle at an angle, and the newer, digital photo showing the ‘Floater’ straight on, you will notice some striking similarities, as seen below.

Note the Federal Shield appears to be identical; the “glob” left at the seal edges from the impression show definite identical characteristics. Thinking of the applied seal in clock terms, look at the 1:00 position and see the extremely narrow area of globular rim and notice the thickness of the 9:00 position. There is also a bubble in the bottle right next to and at the 10:00 position of the seal in both, although it is harder to see in the older photo, but it is there. Also found is a distinct stretch bubble coming straight down under the front of the applied top on the ‘Floater’ example. The McKearin example shows a similar bubble as well, but the collector’s catalogue number obscures it somewhat. If one could ‘reach’ into the older photo and turn the bottle straight, you would find that these 2 photos show the same bottle. The Charles Gardner Collection was sold at auction in 1975, and bottles from important collections do tend to revisit glass auctions; often more than once. Both pictures show example Number three.

The above examples feature 3 of the possible 6 known Class of 1846 West Point bottles.

Another example that shows up online is one that sold on eBay on 06/18/2007, (my birthday,) and how interesting, because that example ended up at the glass auction where I acquired my example. See below comparison of the eBay photo and my photo, without a doubt, it is one and the same. (Bear with the differences in lighting conditions and slightly different camera angles.) The underside nick at 3:00 on the seal, the “black fleck,” in the bottle below the 7:00 of the seal. It’s actually unmelted carbon and is in the glass on the back of the bottle, but shows clearly through the front. Also note that this example is the only one with the Federal Shield applied at an angle.

So, thus far, I am able to document and have been made aware of 6 examples of this quite historic bottle. I am continuing to network and research. Further developments forthcoming.

Update: See added information below.

My theory so far is leaning towards the very prominent McClellan family of Philadelphia having commissioned these bottles as Cadet George B. McClellan graduated second in the West Point Class of 1846 and his father was a physician and they lived in Philadelphia where these bottles were made. If any Cadet’s family had the means and the societal prominence and cause to celebrate their sons high ranking in graduating West Point that year, the McClellans are first on my list of research. If this theory proves accurate; it will be interesting to know how many of the 59 class members attended the celebration and how many bottles were ordered from Dyottville. This theory, if true, raises the question of whether it was a family gathering with only those fellow class members who could attend the celebration. If so, there may have been a much lower amount of these bottles ordered that my original estimated six dozen, as that amount takes into account the 59 total class graduates and the possibility of an extra dozen bottles ordered.

There are McClellan Family Papers in the Library of Congress and also Penn State University as he went there for the 2 years prior to West Point. The University has papers that date from 1861 forward, but other references I have seen date McClellan Family Papers much earlier than that date. As you can see, finding a reference to a graduation party in 1846 is not a simple task and there are no business records from Dyottville Glass Works that I’m aware of. Below is an excerpt from an email I sent to the Archive Department at West Point, italics mine to help show where it starts and ends:

“The commissioning of a custom embossed private mold was expensive in those days and not practical for a one time order of a very limited amount, so, by using the standard stock whiskey mold, the Cadet father or family member could inexpensively commission them seal stamped. I suspect that approximately six dozen or so of these were ordered from Dyottville Glass Works in Philadelphia. I would also logically conclude that the survival rate would be ten percent or less. I also find interesting that the McClellans were a very prominent family in Philadelphia where these bottles were made and that Cadet George Brinton McClellan graduated second in that class. As far as any attempts to research business records from Dyottville Glass Works itself, non exist, and Dyottville Glass Works is, for the most part, currently buried under Interstate I-95 which runs along the Delaware River in Kensington, Philadelphia where Dyottville once stood.

I am working on a serious article in an effort to prove once and for all that these extremely rare examples are exactly what we know them to be. The few of us that own examples of these spectacularly rare and historic bottles are without a doubt as to their being exactly what they are: privately commissioned bottles to celebrate and commemorate the West Point Graduating Class of 1846.

I have read extensively in your very well preserved Archives, especially the Thayer Papers, the years surrounding 1846, in an attempt to find a mention, however small, of a private graduation party for that class in his correspondence. I have not been successful in that area, but was hoping that it may be possible that the Academy itself may have any kind of information, however small. A mention in a letter, a memoir name, any kind of clue or lead, or scrap of information at this time would be of the utmost appreciation. Maybe there may be a Faculty Member, Historian, Librarian, Archivist, or even a former Graduate who could have something to add.”

I am still looking into the original lead given to me by the owner of the Port Isabel, Texas, example in which he stated that these bottles were documented in a Cadet memoir as: “the liquor was provided by a father of one of the Cadets for a graduation party which they called Fandango.”

Stay Tuned: My next step may be a visit to the National Archives in Washington, DC. I have located the exact box and reel numbers for the personal correspondence dating from 1842 to 1847 for the McClellan Papers.