There is water at the bottom of the ocean

Remove the water, carry the water

Remove the water from the bottom of the ocean

Letting the days go by, let the water hold me down

Once in a lifetime, water flowing underground

Into the blue again, into the silent water

Under the rocks and stones, there is water underground

Letting the days go by, into the silent water

Once in a lifetime, water flowing underground

“Once in a Lifetime”

-Talking Heads 1984

There’s a cathartic event, or, cleansing moment, at a point in one’s life when something happens that changes everything. Suddenly your life takes on an entirely new focus. All current questions and distractions as to the why of so many things; the answers self evident or not, no longer have any significance.

For me, it happened in 1975. I was 10. Even then, as young as I was, I was attempting to grasp the uniqueness of the 1970’s. Cars? Long. Neckties? Fat. Sideburns? Strange. Orange living room decor? Creepy. President Gerald Ford’s clumsiness? Both fascinating and fun. At that time I had many questions; not all of which I was able to arrive at my own conclusions. I was always interested in something and read lots of books. But my focus, (or lack thereof,) on all of that was about to change entirely.

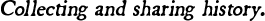

I had just seen the movie Jaws. I had read the book at least twice, but the movie changed everything. I was both hooked and shark bitten at the same time. And relieved from being so distracted. I had found some things about the 1970’s a bit more scary than any man eating monster shark. The radio, for instance, bombarding me with “My Sharona,” by The Knack, now that was really scary.

I became a shark maniac. I had to know everything about sharks. I read every book I could about them. I drew pictures of them. I learned all of their scientific latin names. We had to give a speech before the class in sixth grade that was actually recorded on early beta video. Of course my speech was about sharks, for which I received an A+. I remember sending away for a fossil shark tooth from an ad in the back of a comic book. I also sent away for those “Amazing Sea Monkeys.” At least the fossil shark tooth I received wasn’t a disappointment. It was those two purchases, from ads in a comic book, that taught me the value of caveat emptor at quite an early age.

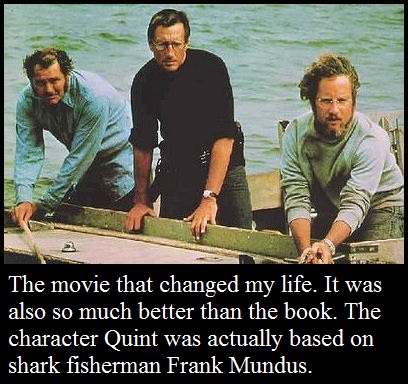

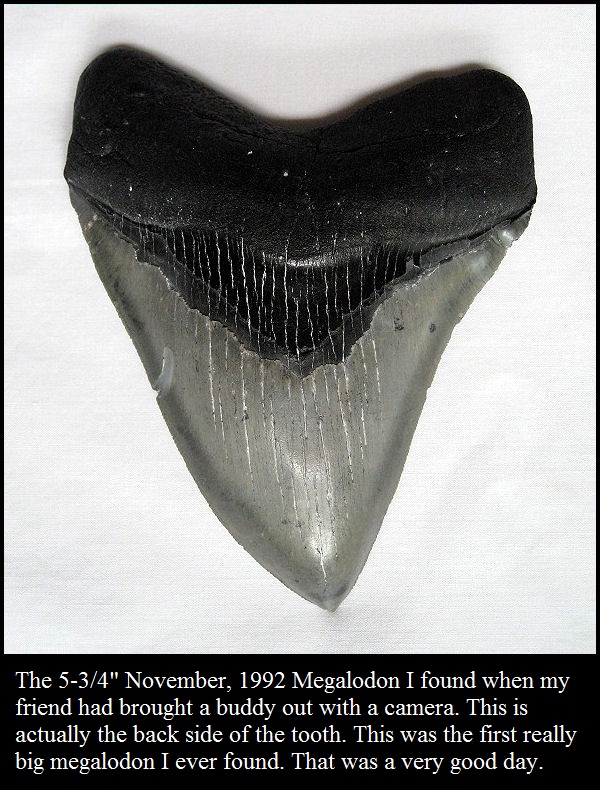

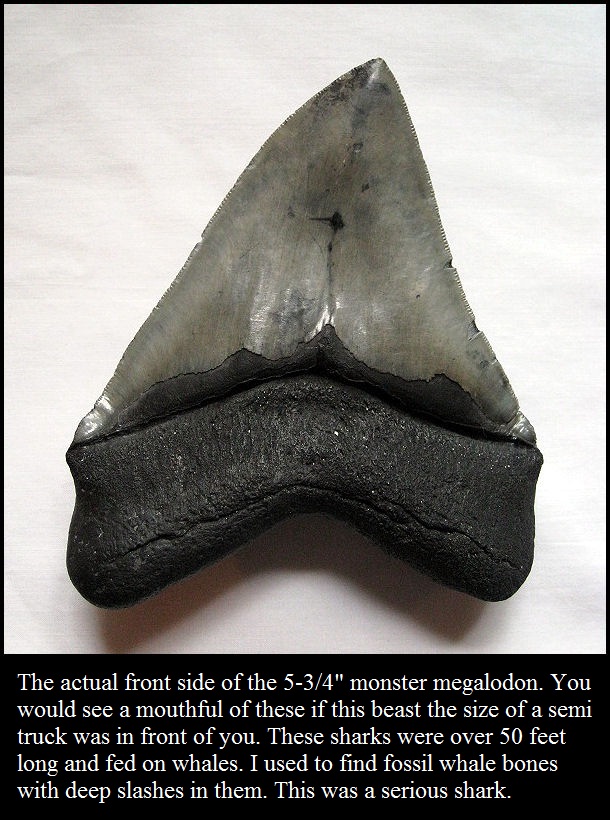

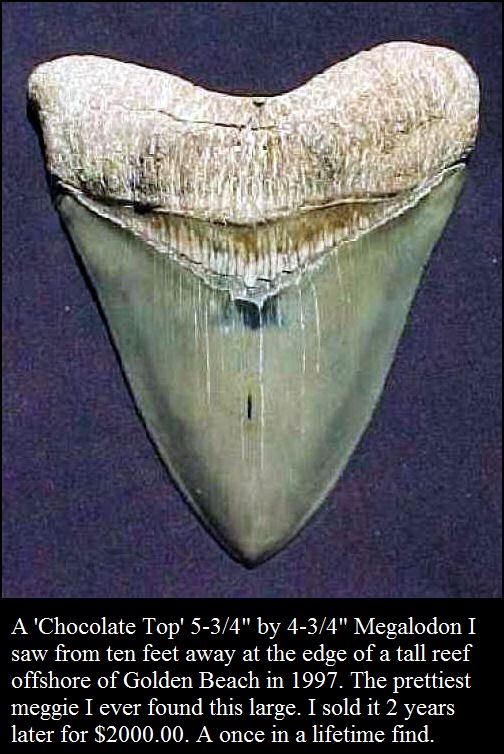

About a year later, we moved from Pennsylvania to Clearwater, Florida, where I became an avid beachcomber, hunting for and finding fossil shark teeth. I can still remember staring in absolute awe at the first really huge Megalodon tooth I ever saw. It was about 6″ long sitting beautifully, in a ‘not for sale’ display case in a St. Petersburg Shell & Gift Shop. This tooth was from a Monster. My life now would not be complete until I had one for my own. This would become an obsession to last for years to come.

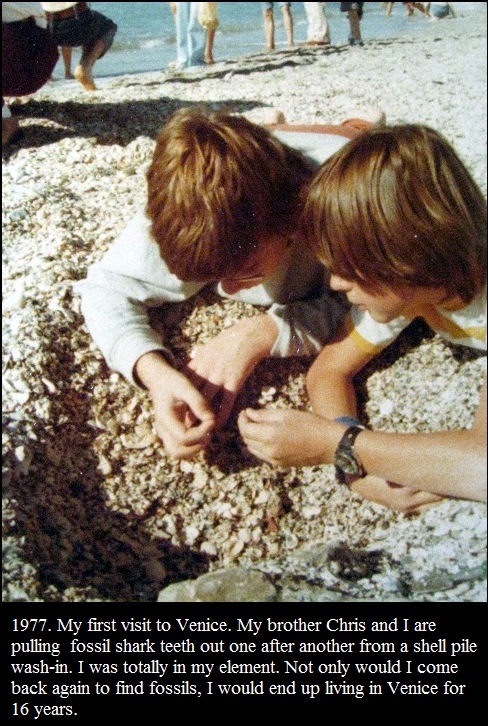

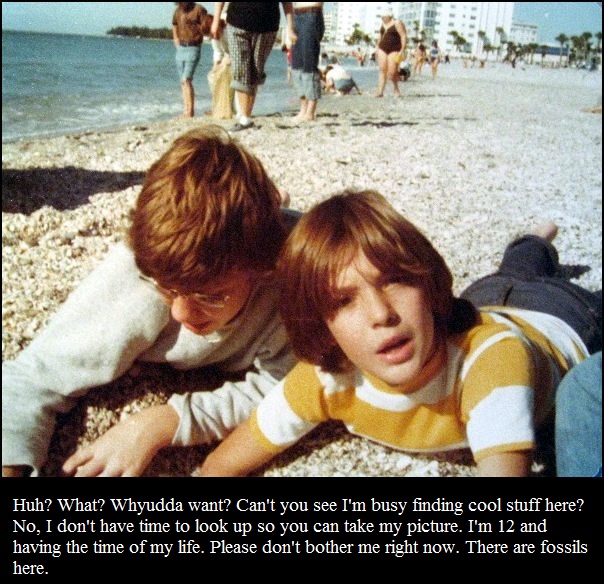

I soon learned of the “Shark Tooth Capital of the World,” a sleepy beach town named Venice on the Gulf of Mexico some 60 miles south of Tampa. I insisted on being taken there and my mom drove my brother and I there for an amazing day in 1977. Throughout my early years I went there as much as possible. I beach-combed and encountered fossils of all kinds literally washed up on the beach there and also, when I was old enough to drive, encountered retired still living fossils, driving literally 20 miles an hour in the left lane too.

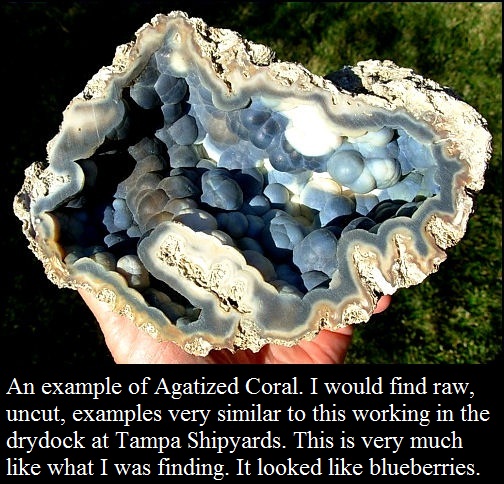

1984, at age 19 found me living in Tampa and working in Tampa Shipyards. First for a construction company excavating the dry dock for the Navy Tankers, which I would later work on as a pipefitter’s helper. During this work deep down in the large pit by Tampa Bay, I could hardly focus on my job. I kept finding all sorts of fascinating items just laying about, literally sticking out of the ground. Agatized coral, strange crystalline geode type examples, no fossil bones, but I was so curious about these geological mysteries. It was hard to do my job with my hands and pockets full of these curiosities, so I began to make hidden stash piles that I would take to my car at lunch break and at the end of the day.

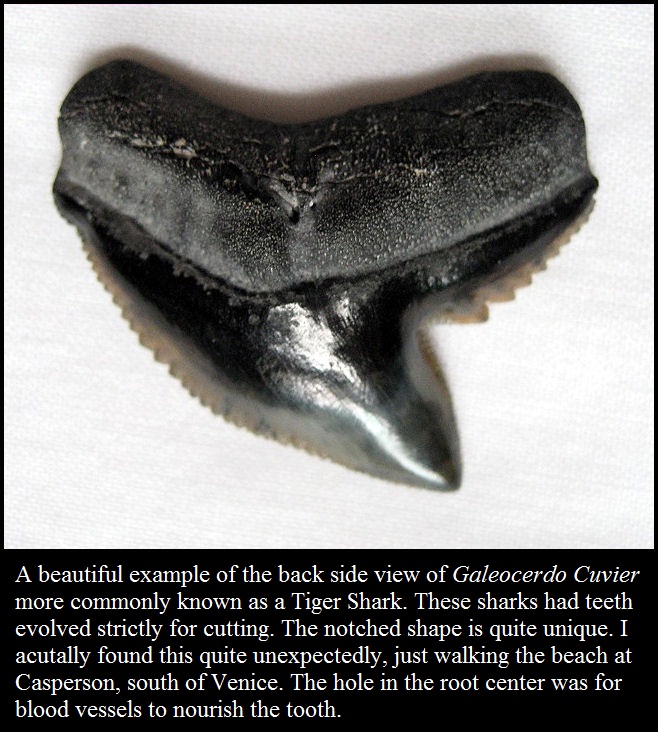

During the weekends, I drove down to Venice to free dive. With mask, fins, gloves and a wrist strapped mesh bag, I would venture out to a depth of about 10 to 12 feet where there were rock beds with bones, whale vertebrates, woolly mammoth teeth, small shark teeth, large shark teeth, all kinds of fossils too numerous to list. They were only occasionally laying clearly about; you really had to look and move rocks and fan, or sweep the sand to uncover them. I would hover above my hole and drop down and work it to the size you could park a car in, with my mesh drawstring bag becoming heavier with amazing fossils. I learned that there was a fossil layer at a certain level in the ground and the depth where I was free diving was once dry land. The land, I later found out, went out for miles into the Gulf during the Ice Age and there was once a river about a mile offshore that the Gulf had encroached over, mixing and scattering a Miocene Era layer of marine fossils such as whale bones and shark teeth. These fossils dated back some 5 to 20 million years. The stretch of coastline in Venice that produced these fossils ran about 5 miles; from the North Jetties separating Venice from Nokomis, south through miles of private beaches ending below Casperson Beach, where the prehistoric finds diminished.

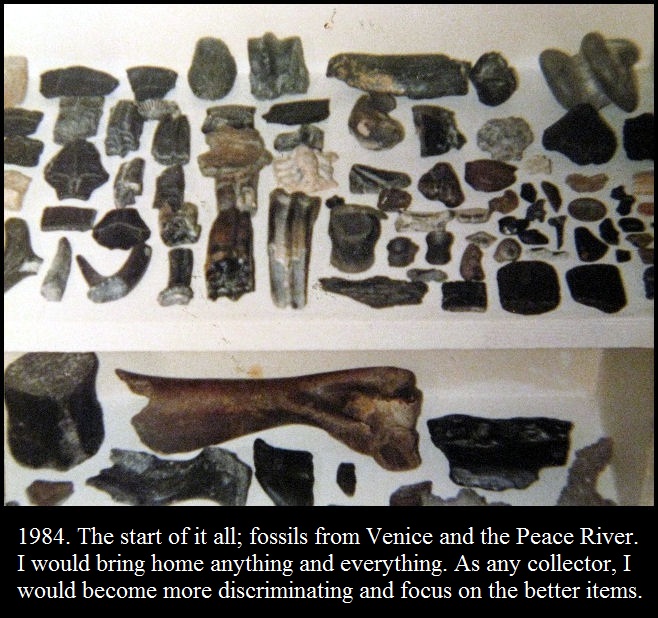

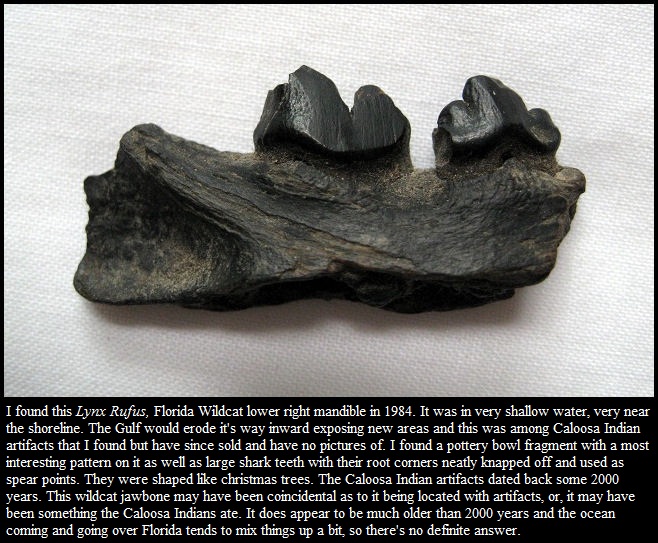

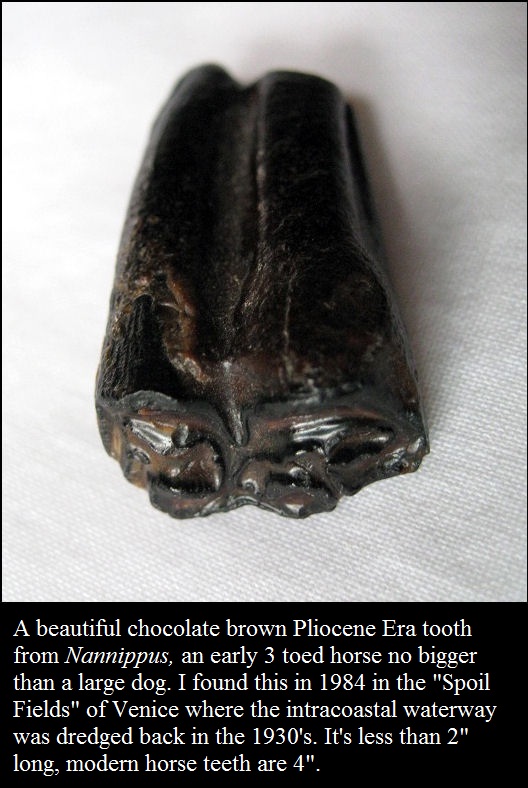

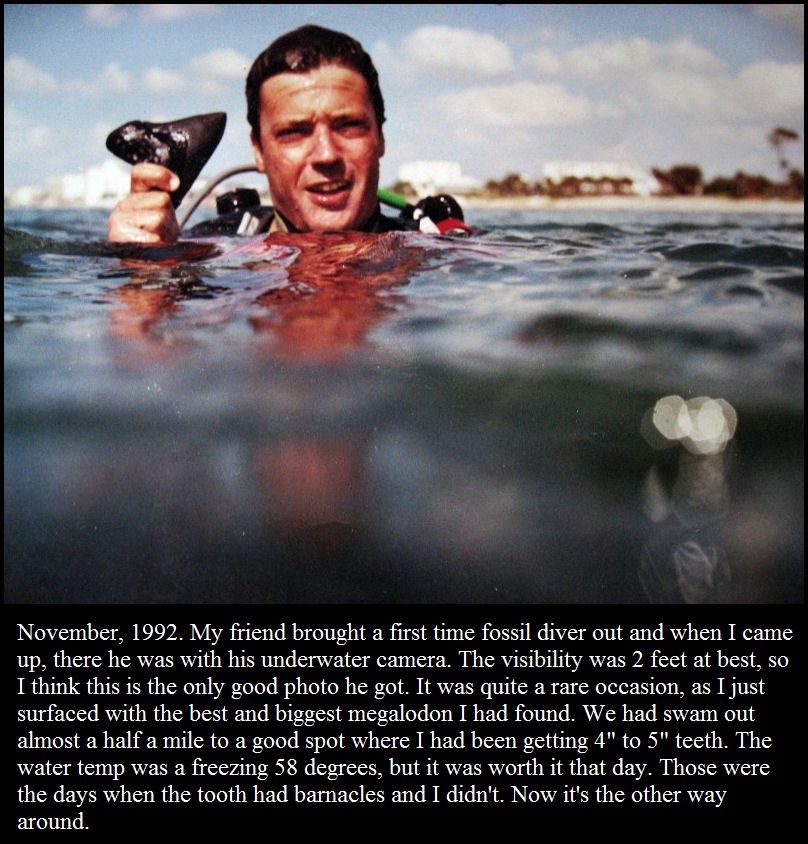

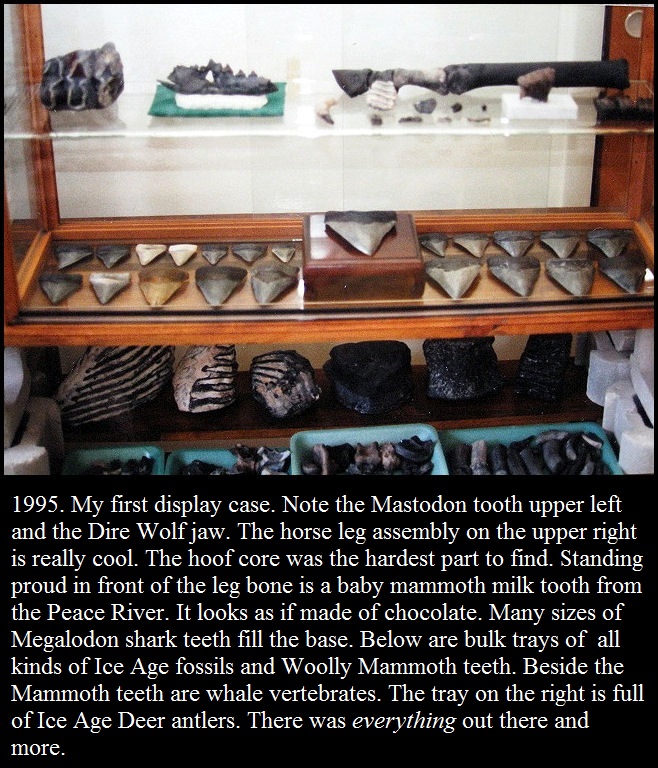

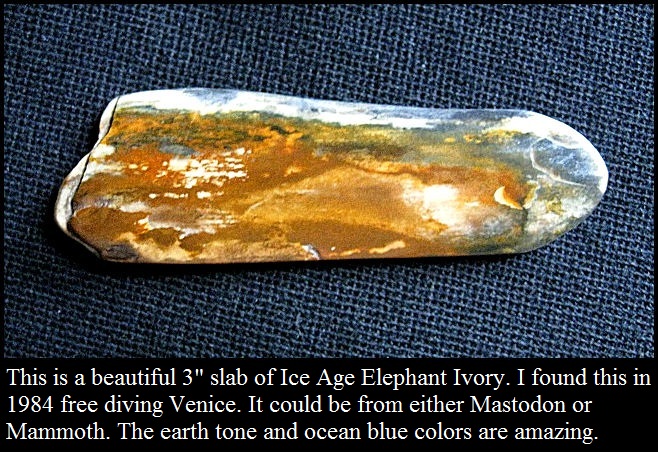

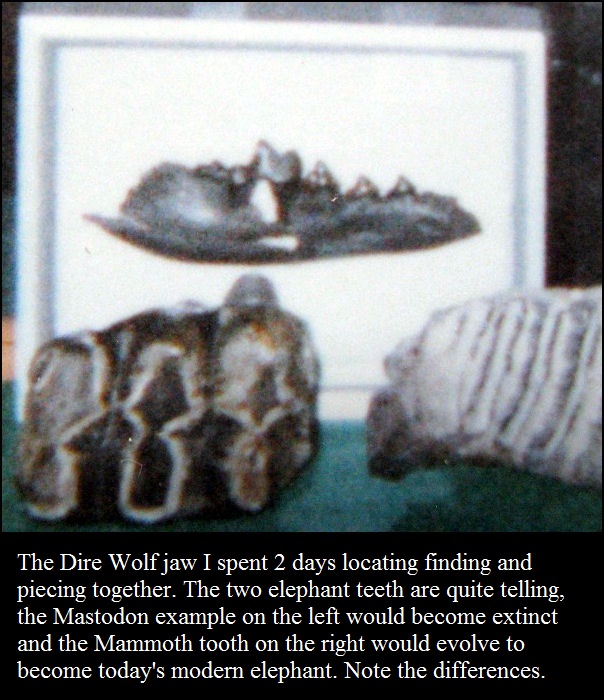

Amongst the scattered mix was also the more recent Pleistocene layer, containing Ice Age mammal fossils. There were remains of everything from mastodons, (an extinct elephant,) to woolly mammoths, saber toothed tigers, armadillo type animals the size of Volkswagens, early three toed horses only the size of a dog, dire wolves, wildcats, giant sloths, you name it. This place was literally an underwater treasure trove of a huge variety of fossils. Sometimes a flawlessly preserved 4″ Megalodon shark tooth would simply be laying there like a present, other times you could fan and dig and move rocks all day and find only a broken piece of one or just the occasional ice age horse tooth. It wasn’t easy. It required work. I learned to train my eye to look for anything with symmetry amongst the chaos of the rocks, sand, shells, and debris. It was at first confusing, then fascinating to find a mammoth tooth near a whale bone, both of quite different ages and origins. When the waters were rough and the visibility was less than 2 feet, you really had to know what you were looking for. There would only be the slightest corner of the root of a perfect 5″ shark tooth exposed and you had to be able to recognize and know the shape and symmetry of just the root corner of a Megalodon tooth or you’d miss out and pass right by it.

I also learned rather quickly, that when the seas were rough, (or too cold in the winter,) or when there was no visibility, (or usually all of the above,) that there were “Spoil Fields,” in Venice. These were large field areas of dredge material from when the intracoastal waterway was dredged back in the 1930’s. These fields also provided more of the same fossils as below the sea surface. You could walk the fields after a good rain and see newly exposed fossils, but the best method was to find pockets of rocks and debris and dig and sift. Some of the fossils from these fields came in unusually beautiful colors. Bone material mineralizes and becomes stone, according to what type of material it comes to rest and fossilizes in. This is true with shark teeth, however the enamel of the blade, which is so molecularly dense, it does not mineralize. It only stains and takes on the color of the surrounding material it became buried in.

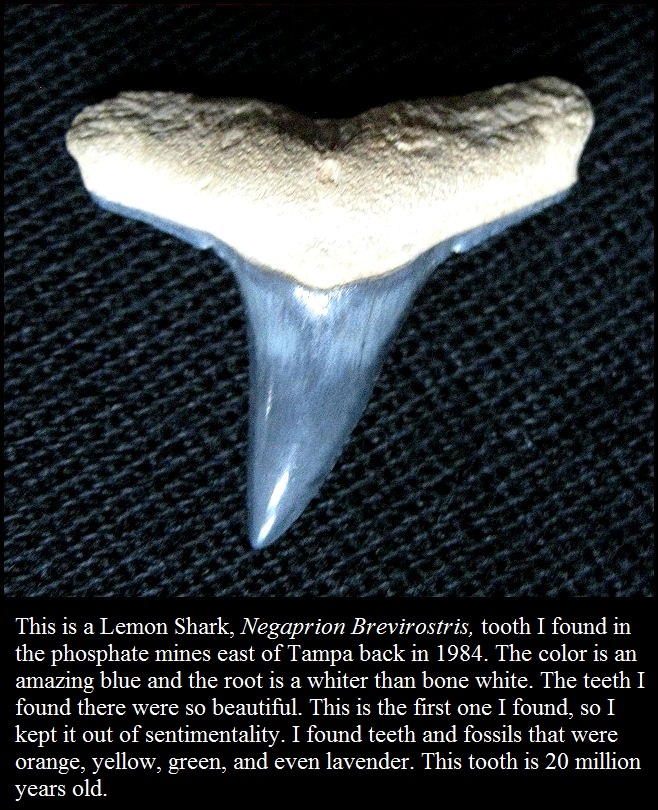

The Phosphate mines east of Tampa, in the Bartow and Mulberry area contained some of the most beautiful fossil shark teeth I have ever seen. Collectors refer to this area as “Bone Valley.” The shark tooth colors range from deep blues, bright orange, yellow, green; it was amazing what you could find there. I once found a 2″ shark tooth that was a pure lavender. Being out in these mines was not without it’s own dangers. I remember being on a mound with a buddy, both of us clearly hearing the distinctly loud rattle of a large rattlesnake we could not see. We stayed on the mound and threw rocks in the sound’s direction until we heard silence, and waited some more before coming down. The shark teeth we found were worth the danger risks. These now impossible to get beauties fetch quite the high dollar on the market. The ease, however, of acquiring these was back in the mid 1980’s and sneaking into the mines went mostly unnoticed, but, if you were caught, you were simply told to leave, so you did, (leave that spot and sneak into another area that is.) Years later, it became serious; getting caught meant being thrown out and likely fined, and arrested. I was glad to get some of the goods when the gettin’ was good.

By 1989, I was living in Venice. I was doing extremely well free diving and was getting tired of “weekend” scuba divers following me around while I free dove and dug my holes and bagged the goods. Newcomers who can’t sniff out the fossils for themselves always seem to sniff out the guy who’s onto a good spot that he’s earned by his own hard work. I would find this to be a problem for the next 15 years. At the time, I was working for Amtrak on their Tampa to New York trains and I worked 3 to 4 days on, and was off for 3 to 4 days. Boy, talk about living the good life, this was the best I ever had it. So, with a decent income and monies from selling shark teeth to tourists on the beach, I decided to get scuba certified and do some serious fossil hunting, out in the deeper waters where the submerged riverbed was.

I received my SCUBA certification in May of 1989. I was 23 years old and now an Open Water Diver, allowed by my certification to dive in depths of up to 60 feet. The Gulf of Mexico, off the coast of Venice, was much like a large, shallow lake, you could go 2 miles out and it averaged about 36 feet deep. My experience free diving and the breathing of compressed air actually expanded my lung capacity. I remember my girlfriend at the time, (who I met in dive class and later married; we were together for some 15 years,) timing me holding my breath in a pool at my apartment complex. I stayed under for just over 3-1/2 minutes. Diving in depths of 36 feet and under can be quite safe; you’re in the same “atmosphere,” and decompression is not necessary. Going deeper, nitrogen will build up in your bloodstream and you have to come up gradually and wait for periods of time at certain depths to release the nitrogen, thereby avoiding the bends. The main thing to remember in any depth is to never hold your breath when ascending (compressed air expands coming up,) and it was also a very good idea not to rise to the surface faster than your bubbles. Point being, I could dive all day at the bottom safely, finding fantastic fossils and most occasions would get 1-3/4 to 2 hours ‘bottom time’ on a tank.

I usually did three dives a day, averaging some 6 hours on the ocean bottom. If I was on a hot spot, or new exposure, and wanted to clean up before others knew what I was up to, I would do four dives. This began as a challenge as I started out with only a motorcycle and one scuba tank. I would strap the tank and my duffel bag of gear across the seat against the backrest of the bike. After each dive, I’d zoom back to the dive store for a tank refill. I was definitely a unique sight in Venice as my dive flag stuck straight off the back of my bike. There was risk if an accident occured; the tank with 3200 pounds per square inch of air would go boom. This, of course never did happen, I was quite careful. I later progressed to a van, then just a car.

The diving “rule” was to always dive with a buddy, but this was finders keepers diving. There was an unspoken rule in the earlier years amongst a handful of us “Dive Buds” that whenever one found a spot we’d hit it as hard as we could, then of course show off our finds and offer to “invite” the others to check it out. There seemed always enough to go around. In later years however, when pickin’s got slimmer, we became more crafty, and would make our discoveries more private. In the early years, I dove alone all the time and when I did go with a friend, we went to to the same area, but gave plenty of room and kept away from each other.

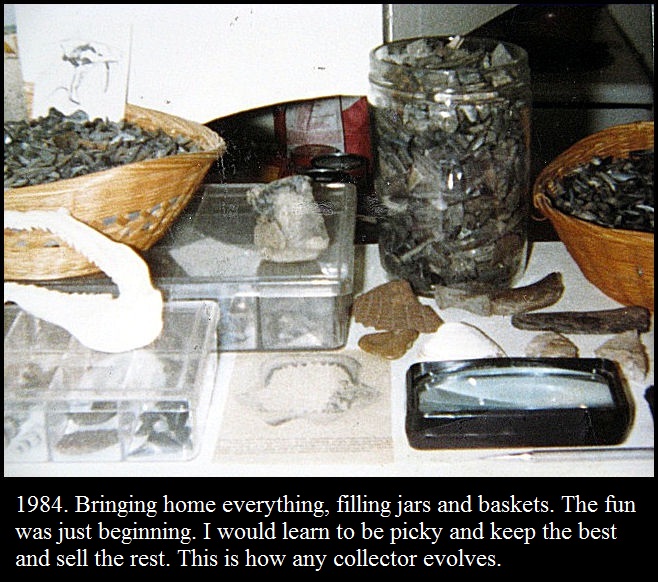

The amount of finds I brought home began to pose an issue as to where to put it all. I began by simply building easy and cheap board and block shelves and also found that Styrofoam produce trays from the grocery stores were both fast and easy methods to store all varieties of fossil bones and teeth, which I was finding in large bulk amounts.

As my shelves filled, I began to network and found wholesale buyers, some local, but the best were out of state dealers and folks who worked at museums. I was selling unsorted whole and broken jewelry sized, (3/4″ to 1-1/4″) shark teeth for $65.00 to $75.00 a pound, depending who was buying.

There were plenty of days where I would go offshore and just pick the old river gravel beds, just picking up small shark teeth. It was basically work, but the surface water temp in the summer was 86 degrees and at 2o feet down, it was just comfortable. I would literally creep the bottom, plucking and bagging, just like picking berries. After 6 hours, I would have up to 10 pounds of teeth, sometimes more. Making $600.00 plus a day plucking fossil teeth off the bottom of the ocean was the most fun money I ever made. It became a choice; where the small debris and particles were, there were no large teeth like the Megalodons. Everything gathered by size on the bottom, where there were big rocks, there’s where the big fossils would be. So it was my choice; to go for steady money by picking berries in the gravel beds, or go exploring around the reefs and boulders chancing for a whopper of a Megalodon or Mammoth tooth. The giant megalodon teeth were not as often found in the Gulf of Mexico as they were in the rivers of South Carolina.

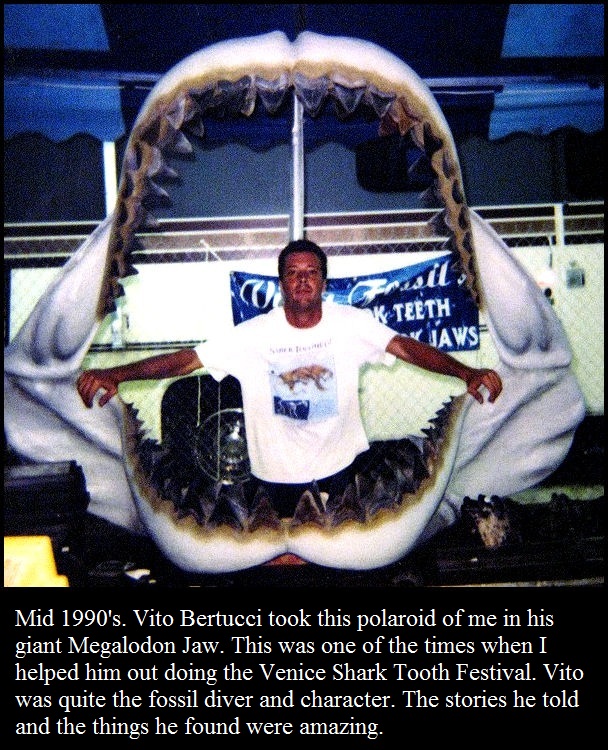

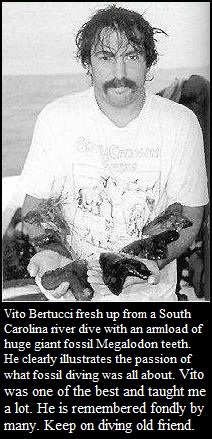

By 1992, I was very experienced and finding some real nice fossils. I was also making some real good friends with fossil collecting interests. I was also taking high volumes of teeth to the dealers from out of state who were doing the local Venice “Shark Tooth Festival” trade show and making a killing each July. The renowned fossil diver Vito Bertucci from South Carolina would always arrive just as the show was beginning and set up his fantastic giant Megalodon Jaw. He always came alone and always appeared to need help, unpacking stacks of produce tomato boxes filled with giant teeth and amazing fossils and for 2 years in a row, I would help him run his booth and do the show. He would either pay me cash or in large megalodons. I did some incredible trading with him and others; bulk amounts of small jewelry sized teeth that I found so easily for huge 6″ megalodon teeth, which the Carolina diver found in quantity in the low country rivers there. It was helping Vito that gave me the experience needed later when I would do the show myself and have my own booth. I never met a fossil diver with such passion, or enthusiasm as Vito. He was even featured on National Geographic. I last saw him when doing the Festival in 2003. The next year was a sad, tragic one. In 2004, Vito would die of a heart attack at only 48, while diving a deep hole in the Ogeechee River, near Savannah, Georgia. He was diving under treacherous conditions with a ten foot tide current and was wearing a weight harness of some 140 pounds to stay on the bottom. He passed from this world doing what he loved best.

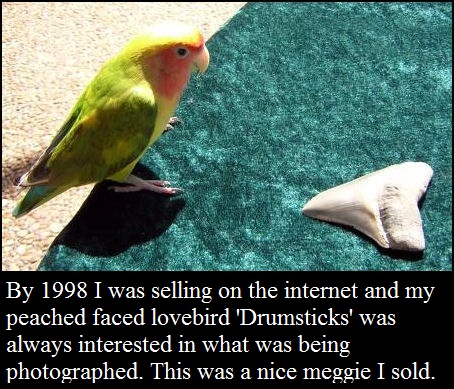

After learning the ropes from helping Vito, I started doing trade shows and was still wholesaling by the pound, making necklaces, selling large teeth to locals and tourists. Most folks don’t realize how much money there is in fossils. There was and still is quite a market out there; from collectors, to museums, tourists, beach gift shops, dealers at trade shows, it’s almost endless.

There were a couple of local fossil dealers who would buy basically everything I could provide. I even partnered together with one, first for the biggest Fossil, Gem and Mineral Show in Tucson, Arizona, in 1997. It’s every January and it lasts 2 weeks. Your hotel room is your booth. It was and still is the most amazing show as there are dealers from all over the world. I also partnered with this local dealer for the biggest and coolest idea that unfortunately turned out to be a crashing down to earth blunder; meteorite necklaces. We were convinced that Air and Space and other museum gift shops and other stores would do very well with them. I even proposed the item to Spencer’s, a renowned “Mall” novelty store. Our wholesale cost was too high for them, although they liked the idea. It was a great idea, just a bit ahead of it’s time. I made thousands of these necklaces with meteorites bought in bulk from Uraguay. There is a giant field down there in Paraguay where a meteor shower occurred some 5000 years ago. The exploring Spaniards came across it in the 1500’s and named it Campo de Cielo, or “Field of the Sky. I made sure to make a nice necklace for myself, which I still have, the meteorite being a bit bigger than the examples on the necklaces we were selling.

Fossil diving was an incredibly fun way to earn a living. The only issue was the weather and water conditions. You simply couldn’t dive every day. Mostly in the summer you could, but the winter was another story. The winter water temperature fell to the mid 50’s and it was both bone chilling and teeth chattering cold. I remember physically shaking uncontrollably, coming out after a winter dive, even with a 2 piece overlapping 3/4″ wetsuit on. So it was a seasonal catch as catch can situation. In the winter, we tended to dig the spoil or dredge fields, where the finds were nice, but fanning sand underwater is much easier than shoveling and sifting it on land.

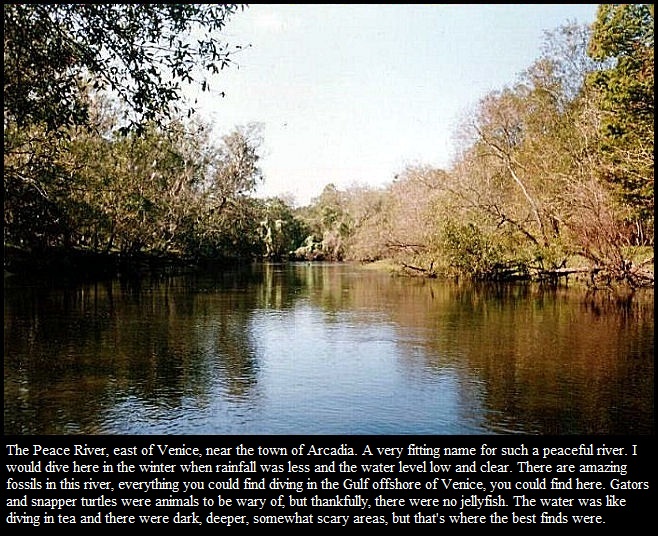

Although the water was colder in winter, there was also very little rainfall. This made the rivers run lower and shallower. The Peace River was about an hour east of Venice, out near the quaint antique town of Arcadia. With a wetsuit, you could stand it for a while, and then sun yourself warm on the grassy banks. The fossil finds there were similar, the colors of the bones and teeth being a brown and gray with little variation. I remember a little baby woolly mammoth milk tooth popping out of a hole that looked like it was made of chocolate. The water was tannic from the leaves and it was like diving in tea on the best days. Sometimes it was just plain dark and scary if you went deeper in areas, but that’s where the good stuff was. Alligators and large snapper turtles were always on our minds and were sometimes seen, but they seemed more scared of us than we were of them.

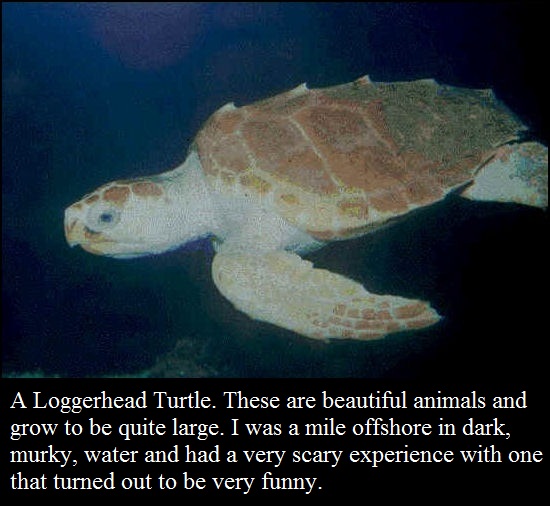

Diving the Gulf, there were always sharks and all kinds of fish and animals around. The sharks tended to keep their distance as the bubbles from the regulator made a loud clattering sound as they rose and expanded to the surface. (Imagine the sound of bowling pins being knocked down and that’s what your breath sounds like rising to the surface.) Bottle nosed dolphins were very friendly and sharks don’t like them for some reason. There were always those dolphins around, if not seen, you could hear their very distinct “ping-squeal” sound. Loggerhead turtles were plentiful, especially during their mating season.

I’ll never forget the one time I was scared out of my mind. I was about a mile offshore, diving off my 12′ ocean kayak, when, in the dark, murky 4 foot visibility, I felt something large pressing against my tank from behind. I sped foward and turned around to see this large brown and yellow turtle vertical, with it’s belly facing me. (Thank God it wasn’t a large shark.) I instinctively kicked up some silt and gave myself some distance. A huge turtle had come up behind me and attempted to “mate” with me. Sea turtles are very cute and all that, but they’re definitely not my “type.” Back up on my anchored kayak eating lunch, then switching out tanks, I realized how funny it was.

I was once briefly circled by two five foot Blacktip sharks, but that was all, they apparently lost interest and went away. There was a really cool barracuda with a very distinct scar on it’s side that I saw more than once. I was stationary, fanning a hole and looked up and there he was, about five feet long, just hovering above and in front of me, looking to see if I had dug him something to eat I guess; after a moment he casually swam away. I saw him again in a different area a week or so later, he just seemed curious. I didn’t see him after that second time.

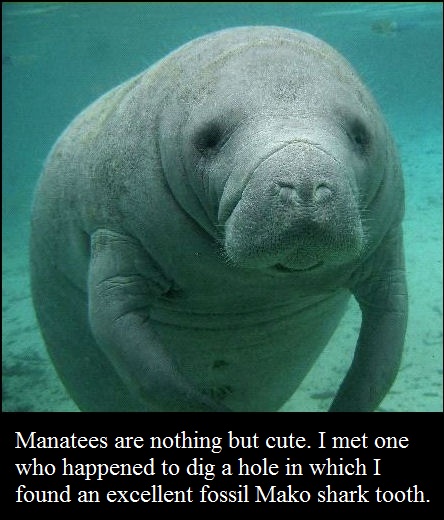

Another time in dim 4 to 5 foot visibility, I saw what I thought was my dive friend nearby, a large dark figure lengthwise facing the bottom. I swam closer to see, and it was the largest, cutest manatee you ever saw, with a big cow like, almost puppy dog cute face. The manatee was fanning the bottom for crabs or food. He turned his head to look at me and stopped and then turned and swam away. I looked at the hole that he fanned and there was a beauty of a 2″ plus fossil mako shark tooth freshly exposed. I remember thinking, what a nice manatee, to dig that tooth up just for me.

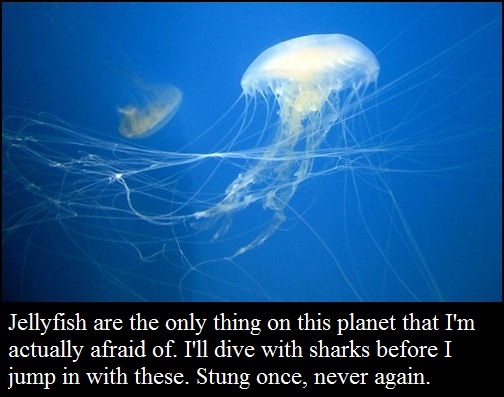

The only things out there that did scare me were jellyfish. If you’ve ever been stung, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about. It feels like a an open flame on your skin for hours. I was diving in the summer time, (just diving in shorts and dive vest, which held the tank,) and I was in a real good new exposure, scoring awesome teeth when I looked up and I could see about 15 feet around clearly, and there were jellyfish all around. I thought, man, this is a good spot, if I can just not let one get close to me I’ll be okay. I turned and braced against the bottom with my tank and kicked my fins to sweep a current and clear them from around me. That worked for a while, but I didn’t notice one get in front of me near the bottom where I was fanning. I swept it right into my chest and across my upper bare left arm. “Ouch” just doesn’t even begin to describe the pain. It felt like I was on fire for hours, even after I got ashore. An oldtime gal on the beach saw me grimacing and she actually got a little container of “meat tenderizer” out of her beach bag and applied it. It actually helped, but not completely.

Having started out swimming offshore with an inflatable vest and then dropping down, alot of the dive folks I knew ended up investing in boats, with GPS so they could tell the exact same spot to hit again if it was a good one. I, being more of a naturalist, (and not wanting the expense of owning and towing and upkeep of a motorboat,) bought a 12 foot “Ocean Kayak.” I had a Toyota Corolla and I could simply strap the kayak to the rack on my car roof and all my dive gear, 3 tanks and all, fit into the trunk. It was less expensive and definitely a more easy and simpler way to go. The kayak fit all three tanks and gear and with a red dive flag masted on the back, off I went out into the sea, to spend the entire day out there. The money I made from fossil diving along with having an antique store with my then wife would buy us a very nice house.

Not having a GPS unit like the other divers didn’t slow me down a bit. I did it the old fashioned way, and used a method I called ‘Indian method’ to locate the same spot again. Some divers referred to this as ‘Triangulation. I would come up, note 3 or more landmarks and see how they lined up. There was the town watertower, condo buildings and trees, the end of the fishing pier, etc. All I had to do was note how three things lined up and I would know where I was in a general sense, but I became very good at it, as the find of the Dire Wolf jaw would prove. It was June of 1995 and I was straight off the public beach but it was tricky to know just how far out. I had found 3 sections of a dire wolf lower jaw that almost fit together in a clay bed of the old river well offshore. I had found it on the third dive and came up and noted with triagulation where I was. The next day I wanted to go there again and went out until I noted the same 3 part line up of landmarks. I dropped down and lo and behold if I didn’t find 2 more parts of the same jaw which enabled me to fit it all together.

The problem for me was that by the year 2000, diving Venice for fossil shark teeth had become so popular that there were now dive charters who would take a group of “tourist divers” out for $60.00 a head. These charters, one in particular, would become a real thorn in my side, as I would be out on a good spot I found on my own, holding my 7 pound anchor and towing my kayak above me as I went, only to hear the very loud underwater sound of it’s motor as this charter boat came close to me and (of course) the numbskull clicked his GPS on my spot. I knew this because the next morning this charter boat would be exactly where I was the prior day and still wanted to go. I then learned to go a bit off from my spots and leave my kayak anchored over a sandy desert floor and swim off to the exposure. You can’t hide a 12 foot blue kayak with a red dive flag sticking up 2 feet off it’s stern. Even before getting the kayak, I had to (by law) have a dive flag marker, so boats know you’re down below. It’s also a marker to locate the body if something goes wrong. If I was on a good spot then, I would wrap my flagline shorter and pull it under water. I don’t recommend this as it’s not safe, but when you take the time and effort to find the virgin, jackpot spot, it’s only your spot until someone else hits it, and outside of my small circle of dive friends, things can get real competitive out there.

It was in the early 2000’s when the Army Corps of Engineers “renourished” the beaches all along the coastline of Venice. Large barges pumped in sand from 3 to 4 miles out to create a new beach which extended out to cover some good areas, now buried for good. The Gulf had eroded in almost right up to the expensive homes and condos. This changed everything. Now a boat or kayak were an absolute necessity if you were to find anything significant at all. Gone were the places where I once swam out and dropped 16-20 feet down and followed the changes to the bottom patterns and exposures of new fossil beds. I still dove and did okay, I just did it a lot further offshore, usually a mile or more in my kayak. But it wasn’t the same, the exposures out there had megalodon teeth, but most were of very poor quality, and it was only occasionally that you’d find one still serrated and collectible. The fossil diving heyday was pretty much was over for me by 2005, it became a lot of work for too little reward. I found my life moving in other directions as well, which included leaving Florida for good.

In 2008, I did some exploring at Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, and it was an absolute blast to explore the cliffs there and find the old fossil bug in me again. And find fossils too. I guess it’s like that old sayin’ about riding a bike. You never lose it.

Stay tuned, more to come…. Virginia and on to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Fossil Preview:

Below is a very large shale slab exhibiting fossil ferns dating back 300 million years. Found in the area of St. Clair, Pennsylvania, these are from the Llewellen Formation, dating to the Paleozoic or Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) Period. The ferns are white as they became pyrite, then pyrophyllited into Aluminum Silicate. Cool Stuff… Way Artsy too…