The Flask Maker

It begins with a disembarking step ashore in Philadelphia by a 25 year old Englishman. Having travelled by way of London through the West Indies, carrying with him his apothecary formulas for drugs and medicines and a most assured determination to be successful, he would, unbeknownst to even himself at that time, venture forth to become one of the most prolific and successful names in American glass manufacturing history. The year was 1805 and the man was none other than Thomas W. Dyott.

The predominating written history portraying him as arriving poor, or virtually penniless, and renting a cellar with a room above for which he engaged in manufacturing boot blacking at night and applying during the day starkly differs from his actual reality. This was no Horatio Alger story of a young man “Making His Way.” It is apparent he already had big plans.

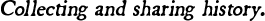

Only two years after his arrival, he was listed in the 1807 Philadelphia City Directory as operating a “Patent Medicine Warehouse.” To be listed that year, he must have been doing a lucrative enough business to have had the business listed in latter 1806 when the City Directory information for 1807 was compiled. It is quite obvious that he had knowledge of medicine and was likely an apprentice to an druggist or doctor prior to his arrival in Philadelphia. He may have also manufactured liquid boot blacking as most on the market at that time consisted of paste. By 1809 he was listed in the City Directory as the owner of a Medical Dispensary on 116 North Second Street, and in 1810 he was listed with the title M.D. It’s probable he was using the doctor title sooner than that, as he claimed to be the grandson of a “Dr. Robertson” of Edinburgh, Scotland, although it was researched that no such “Dr. Robertson” had ever existed in Edinburgh.

By 1810, Dr. Thomas W. Dyott was not only producing such medicinals as ‘Dr Robertson’s Stomatic Elixir of Health,’ and ‘Patent Stomatic Wine Bitters,’ he was charging expensive prices for these assorted bottled medicines and bitters. Prices ranged from $1.00 to $2.00 a bottle and the good doctor was doing quite well for himself. He had his own small flint glass bottles produced in his own commissioned private molds.

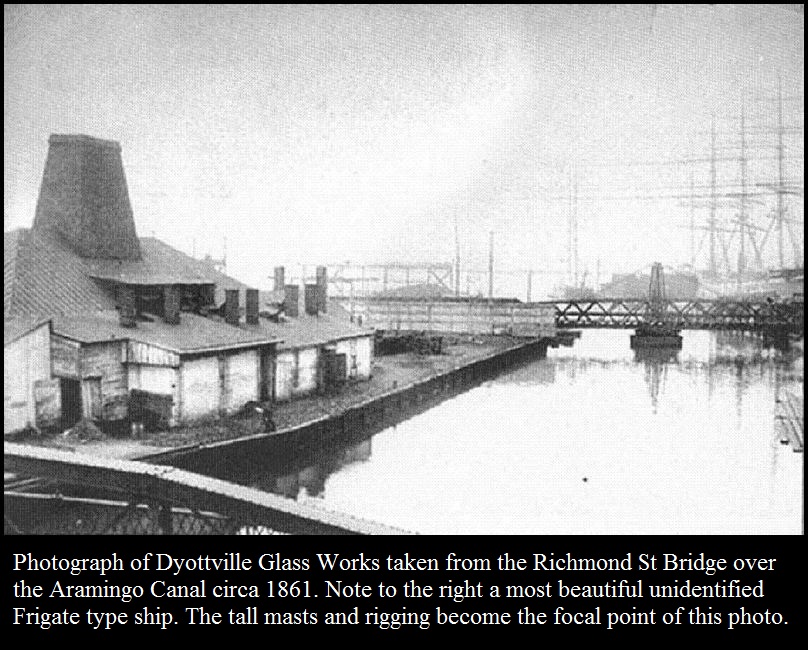

Between 1810 and 1820 his practice and business continued to flourish. Finding himself in need of better quality glass as he was of the opinion American glass at the time was inferior to that made in Bristol, England, Dyott then began buying up interests in various surrounding Glass Works in the Philadelphia and New Jersey areas. Importing English glass was not only expensive, but the War of 1812 had certainly put a damper on things. By 1821 he was, not surprisingly, the proprietor of Kensington Glass Works, Philadelphia, situated right on the Delaware River. By this time he had agents in many cities and states. The initial need for both quantity and quality of glass driven by his success as a medicinal seller and doctor, had led him to discover the glass manufacturing business to be even more lucrative.

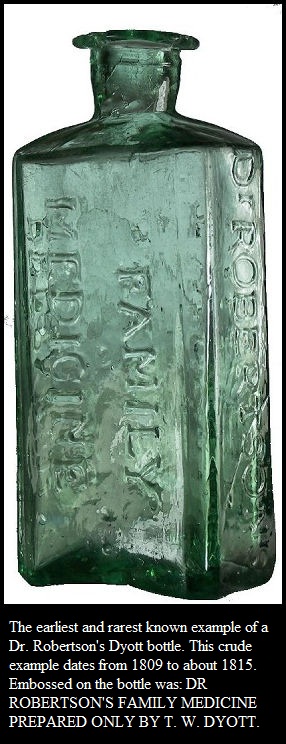

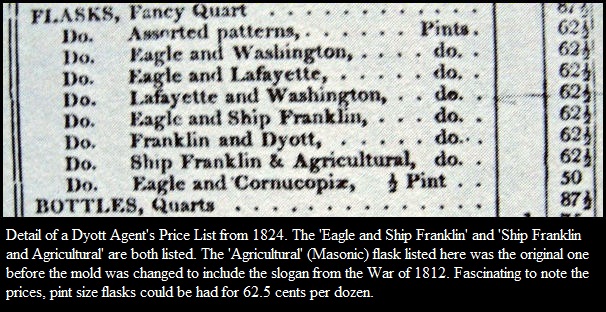

By acquiring controlling interest in Kensington Glass Works in 1821, his initials began appearing on figured and historic flasks produced at Kensington Glass Works. Issued to his Agents in various cities and states were price lists that named Dyott as proprietor. Note in the detail of an 1824 Agent price list shown below, there is a flask that is referred to as ‘Franklin and Dyott.’ This is fascinating, as apparently his initials were not enough. He became the one and only glass manufacturer ever to feature a portrait of himself on his flasks, and, on the same flask sharing a portrait with none other than Benjamin Franklin. Note in an 1825 ad further down that Dyott has now placed his name before Franklin’s and it is now a ‘Dyott and Franklin’ flask.

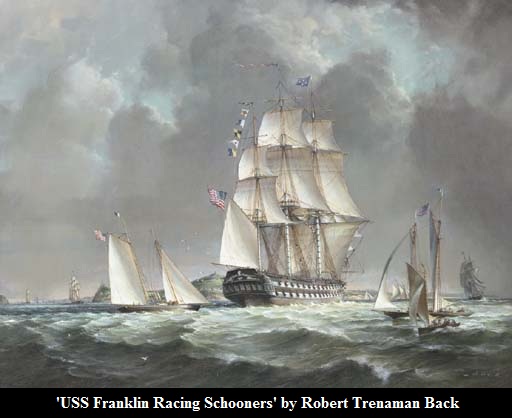

In a Dyott Agent’s price list from 1824 there were many glass wares featured, but there were two that prove most interesting. One was a pint flask referred to as ‘Eagle and Ship Franklin,’ and the other, ‘Ship Franklin & Agricultural.’ Both were identical on the front, featuring the USS Franklin Frigate. On the reverse was, on one an American Eagle, and on the other a Masonic Arch within which were agricultural tools and symbols of harvest. The Ship Eagle flask only saw production from 1822 to 1824. The Ship Agricultural Masonic was produced from 1823 until 1824, when the mold was altered to include the the inscriptions ‘FREE TRADE AND SAILOR’S RIGHTS’ and ‘KENSINGTON GLASS WORKS’ on the flask sides, the ‘Free Trade’ and ‘Sailor’s Rights’ were references to the War of 1812. The flask without the side embossing was only produced for two years. The side embossed flask was made from 1825 only until 1828 or 1830 for reasons which will be soon become obvious.

By 1825, the Ship Franklin Eagle flask was no longer issued as seen below in an 1825 Dyott advertisement. The reason for this flask being discontinued is unknown, but speculation could reason that Dyott deemed the Masonic flask to be more popular, as most elected political officials were Freemasons and it is possible that given the client companies thus far ordering Ship Franklin flasks; they may have preferred the Masonic version as it was very likely a better seller for their whiskeys or content wares.

The flasks themselves are crudely made and exhibit their primitive methods of manufacture in the early 1820’s. Yet they are also elegant and stunningly beautiful. Below are some photos showing comparisons and features of these fascinating flasks.

The 1815 Frigate USS Franklin

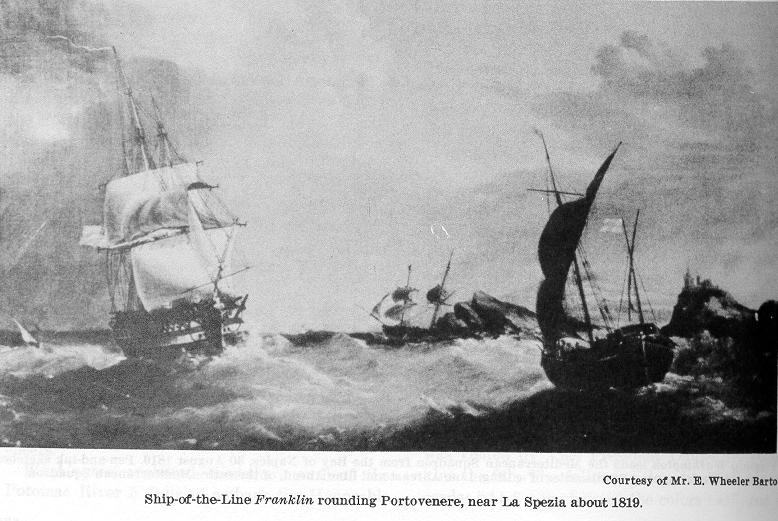

She was built in the Philadelphia Naval Yard and launched in August of 1815. As were most sailing vessels in those days, she was large, graceful, and quite beautiful.

She was also deadly as well, carrying some 74 guns; thirty 32 pound long guns, thirty-two 32 pound medium guns, and two 32 pounder short range cannonades. Comprising a length of just over 190 feet and a beam of 54 feet, she was then the modern day ‘Battle Ship of the Line,’ the term from which the name ‘Battleship’ stems from. The Naval Tactic known as the ‘Line of Battle,’ was a maneuver to bring to bear the greatest weight of the ships guns broadside for an attack.

Her first Commander, Master Commandant H. E. Ballard, sailed her to the Mediterranean where she was the Flagship of the American Squadron. In 1820 she sailed to New York for servicing and then, in 1821, she was en-route to the Pacific where she became the Flagship of the Pacific American Squadron. Now in the Pacific under the Command of Commodore Charles Stewart, who, apparently a most educated fellow, ordered the purchasing of books for the crew until the Navy said in effect, “Enough is enough of all this spending the public’s money on books.” This resulted with the crew itself taking up a collection to purchase books for the ship. The good Commodore Stewart had started a trend and not long after, libraries became ‘institutionalized’ on U.S. Navy ships.

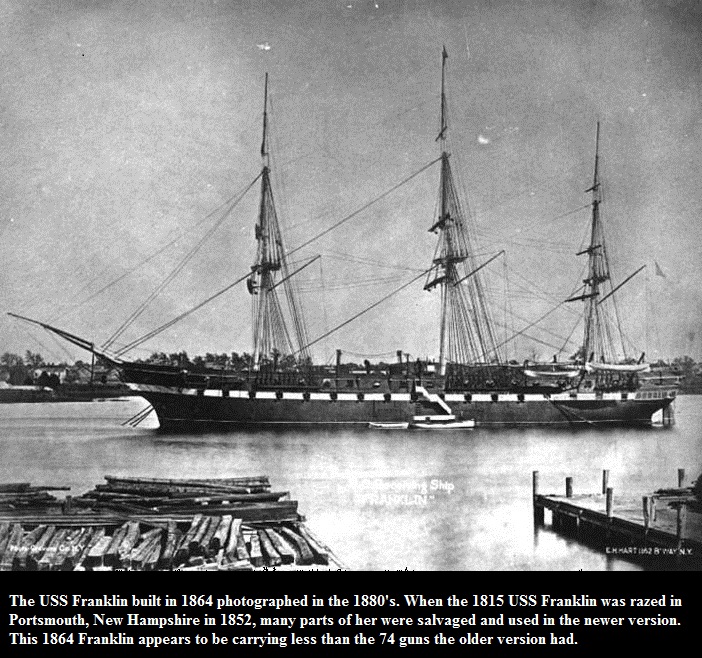

In 1843 the USS Franklin was ordered to Boston to be used as a ‘Receiving Hulk,’ which meant that she was past her prime and would now only be suitable for harboring ‘in-house’ sailors who were waiting to be assigned duty on an active ship. In 1852, she was broken and razed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Although she was old at this point, she still had bulk materials and fittings worth salvaging to offer her new version, the USS Franklin, built in 1864 at the Portsmouth Naval Yard.

The Freemasons and the William Morgan Incident

After examining the two versions of the Dyottville Frigate Franklin flask, and noticing that the Eagle version had only a two year lifespan, and the other, featuring the Masonic Arch and Tools, had a longer but limited lifespan as well, what, you may wonder, do the Freemasons have to do with all this? That’s a very good question and this is where we get to the meat and potatoes of it all; a real, 1826 ‘Who Done it’ mystery featuring the Freemasons themselves.

Enter into the picture a bricklayer by the name of William Morgan, who, born in 1774 in Culpepper, Virginia, and was a Captain in the War of 1812, had moved to Batavia, New York in 1824. Having received the Royal Arch Degree in the Western Star Chapter R. A. M. No. 33 of Le Roy, New York, there seemed an issue of evidence or proof to the Batavia Masons that he had ever received a degree at all. This became a problem when he wanted to join the Wells Lodge in Batavia after signing a petition for a Royal Arch Chapter location there. He took part in Freemason functions, rituals, and gave speeches, but, when the Companions of Batavia succeeded in getting a Royal Arch Chapter in Batavia, somehow William Morgan’s name was absent from its list.

Now stepping onto the scene is one David Miller, also of Batavia. Miller was an Entered Apprentice for more than twenty years, but, up to that time, was denied any further advancement or degree in the Freemason Society. Miller, who happened to be the publisher of the local Batavia Republican Advocate newspaper, had been not only holding a grudge for the lack of advancement, but was also perturbed by his local newspaper competitor, the People’s Press, whose editors, Miller knew, were Freemasons.

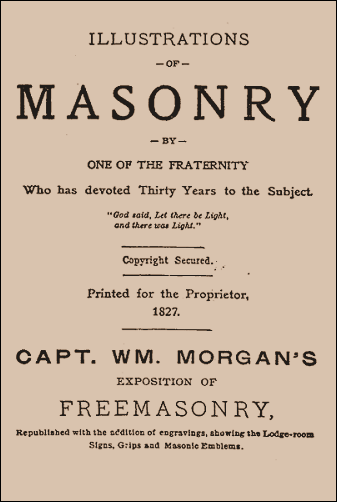

So, now, things get interesting, as Morgan and Miller come to an agreement in which Morgan has decided to write a book exposing the secrets of the Freemasons and Miller is to publish it. Morgan’s landlord, John Davids, and another party, a Russel Dyer, agree to fund the publication and pay it’s author. The book is entitled: Illustrations of Masonry, By One of the Fraternity Who Has Devoted 30 years to the Subject. The book was reportedly at the time to be completely accurate and told of all the Masonic secret passwords, degrees, secret signs, rites, and was also illustrated.

(Below is a link to Morgan’s Book in E-Book format)

http://www.utlm.org/onlinebooks/captmorgansfreemasonrycontents.htm

None of this made for a happy Freemason. There were threats, harassment, much intrigue, and even an attempt to burn down Miller’s publishing office, which almost succeeded. The Batavia Republican Advocate office was set on fire the evening of September 10, 1826. However, Miller, who was apparently forewarned, put the fire without much damage. What occurred next was quite mysterious, and, for William Morgan, most horrific.

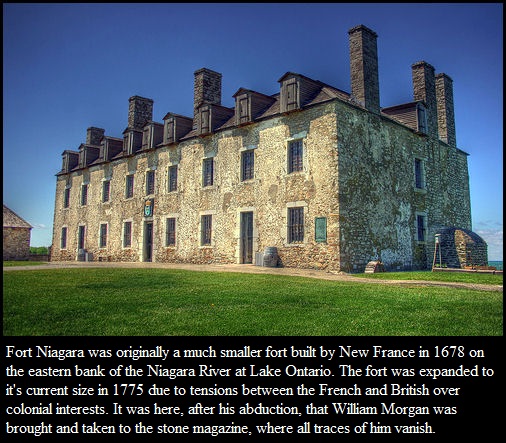

On the next day, September 11, 1826, a warrant was obtained by Nicholas Cheseboro, the Master of Ontario Master’s Freemason’s Lodge at Canandaiga. William Morgan was suddenly arrested for allegedly having stolen a shirt and cravat from a tavern inn where he had rented a room the previous May of that same year. The presiding Judge then released him due to a lack of evidence. Immediately upon release, Morgan was rearrested for a debt of $2.65 due to another innkeeper, which Morgan admitted to and was back in jail that very same evening. The next night, September 12th, Morgan was released due to the debt being paid, either by Miller, as some accounts state, or, by Cheseboro himself, who, as one account indicates, showed up at the jail and talked the jailer’s wife into releasing Morgan. Either way, what happened next is very certain. Upon release, Morgan was abducted by persons unknown and shoved into a carriage, (reportedly a yellow one) which was later traced to Fort Niagara. From there it is reported that William Morgan was taken to the stone magazine in the old French fort and there all traces of him vanish from history.

In later years, between the knowledge gleaned from confusing testimony in courtrooms, death bed confessions, and wild rumours, it is believed that Morgan was offered a sum of $500 and a chance to ‘disappear’ to Canada. Quite the interesting 1826 version of a Freemason, ‘Witness Protection Program.’ There is an account stating that Governor De Witt Clinton, (himself a Freemason) met with fellow Freemasons and offered up to $1000 to make Morgan simply ‘go away’. It remains doubtful, however, that Morgan was given monies and allowed to simply live elsewhere. Some rumours painted Morgan as a Pirate who ended his days of piracy being hanged in Cuba. One alleged death bed confession account in particular states that Morgan was kept in the fort until September 19th and then taken out on the Niagara River in a boat, still alive and wrapped in heavy chains and thrown over the side to drown in cold, dark, watery depths. This is believed to be the most credible account of his end.

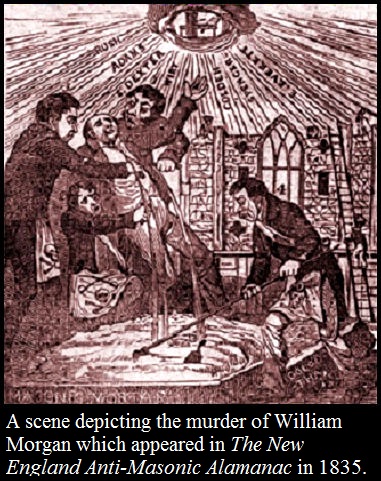

The American public was, at that time, already leery of secret societies and Freemasonry in general. Most prominent people in positions of power and politics were, at that time, Freemasons. With the news of the mysterious William Morgan disappearance, the public became enraged. Freemasonry had just unwittingly dealt itself a very serious blow to it’s former, only simply mysterious, reputation. Now an outraged public believed them to be murderers as well. The backlash against the Masons caused serious everyday strife; friend turned against friend, people took sides most vehemently on the subject. The unpopularity of Freemasonry lasted for many decades.

The immediate backlash against Freemasonry rippled out like the effect of a stone tossed into a pond. Not only did Thomas W. Dyott and other glass manufacturers stop creating flasks featuring Masonic emblems and symbols by 1828-1830, the vitriol towards Freemasonry also went in political directions. It actually created the first major Third Party in politics in 1830, the Anti-Mason Party. Which then resulted into a most ironic situation in 1832. William Wirt, the Anti-Mason Party candidate, had, in effect, split the ticket. This caused electoral votes to be drawn away from Whig Party candidate Henry Clay, resulting in the re-election of Freemason Andrew Jackson. Meanwhile, the anti-Mason sentiment went on for years, creating quite a reduction in the number of Masonic Lodges and members. By the 1860’s it was on it’s way to making a slow comeback.

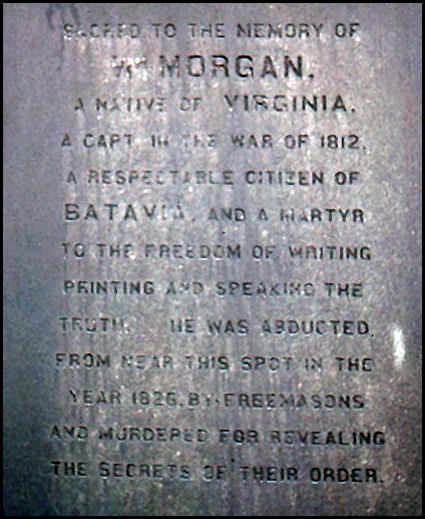

By the early 1880’s, however, the National Christian Association, who, among many others, felt that Freemasonry was akin to a Religion, especially one which left out Christ. The NCA viewed William Morgan as a ‘Martyr,’ “to the writing, printing, and speaking the truth,” and had a monument erected in the Cemetery in Batavia, New York, on September 13, 1882 in his memory.

This article is dedicated to the Memory of William Morgan.