A beginning bottle collector is less discriminating and collects a bit of everything. When I evolved into collecting antique bottles more seriously, I was of the attitude that I would only collect examples made here in America. I wanted the old bottles that were from where I was, with history that was close to home. The towering, 14-1/2″ tall by 5″ diameter beautiful cobalt blue bottle featured above has changed that outlook entirely.

It’s one of the bottles I’ve kept the longest. As a collector, things come and go, but this one has always stayed. It’s the biggest piece of deep blue antique cobalt glass I’ve ever had. I picked it up more than twenty years ago, for only ten dollars in a shop in Florida. I always thought it was a most unique American 1870-80’s druggist apothecary and always held onto it. I had never seen another like it since, either on the market, nor in any book. Occasionally I would ponder it and think it possibly could be a very large master ink bottle, but the applied top lacking a pour spout always dispelled that notion. As an apothecary bottle, it is much more primitive and crude when compared to most American tall apothecaries commonly found in amber or clear. I was never really one hundred percent sure what it was.

Just last week, a friend dropped off (literally on my back doorstep) a stack of old 1960’s-1970’s bottle books he uncovered in his basement; long forgotten and left by his father, who was an old time bottle collector. He was tempted to just toss them, but thought of me. I’m glad he did. Through a nice and simple gesture, he inadvertently helped me solve a twenty year plus cold case mystery.

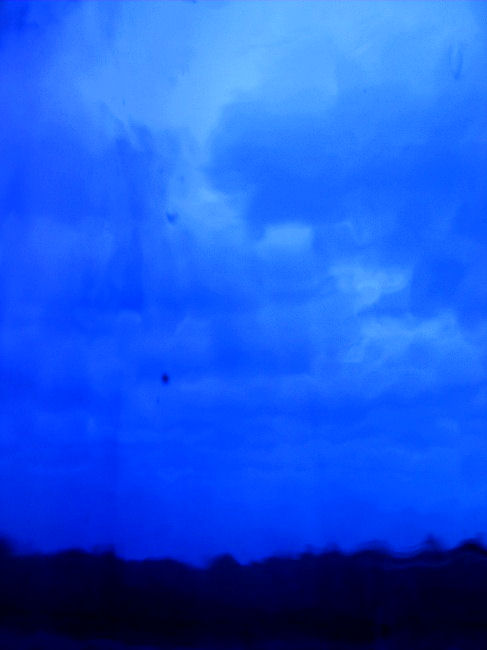

The bottle isn’t American after all. It’s English. It’s classified as a poison or essence bottle by Doreen Beck in her 1973 English book: The Book of Bottle Collecting. Featured on the front cover, it’s the identical match to mine. If it’s a poison, it’s the biggest ever.

Looking a few pages in, it is featured in full color, towering over all the other poison bottles on the page. This exact match to my example along with the others shown with it are from the Roy Morgan Collection. In more than twenty years, this is the first other example like mine I’ve ever seen.

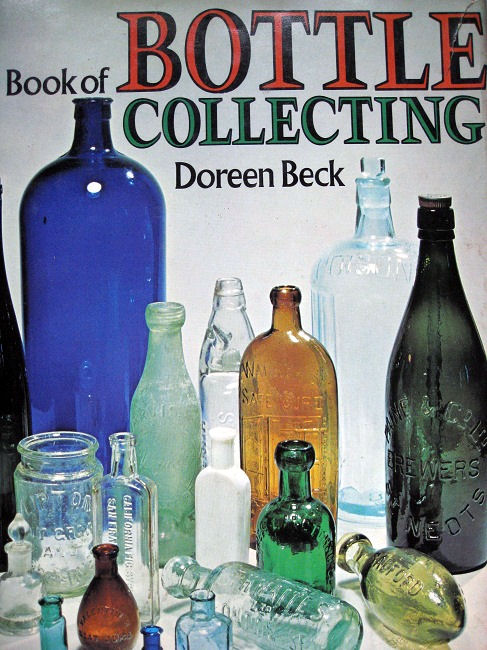

In my earliest years of bottle collecting, I briefly toyed with collecting poison bottles for a while, knowing that the crude NOT TO BE TAKEN embossed bottles, made mostly in cobalt blue, but sometimes in green, were of English origin. The fascinating part was that these bottles I knew to be English were never as old as I first thought they were. The crudity of an English mold blown tooled top bottle made between 1890 and 1930 actually appears just as primitive as a similar American bottle made during the 1870’s to 1890’s. Note the example of an English NOT TO BE TAKEN poison bottle shown below. (Scored, of course, by yours truly in the local Goodwill last year for $1.97.) It looks like an American bottle from a much earlier time, but this example is actually pretty recent, dating from around 1900 to the 1920’s. An American bottle made in this fashion would date to 1870-1890.

In looking at the very large English poison or essence bottle, there are characteristics that date it (even by English standards) to an earlier date. First the top is separately applied, and not merely hand tooled or manipulated.

Second, the mold is 4 part, much like the 3 part mold used by both countries in the 19th Century, the only difference is below the shoulder consists of 2 parts along with the top. Thirdly, there is the extreme ‘whittle’ to the glass. Whittle is what collectors refer to as the appearance of exactly that; the outer surface has the look of being whittled by a knife, or, the bottle came out of a whittled wood mold. Both are good ways to describe the appearance, but the bottle was not carved, and the molds were made of cast iron or brass.

Whittle is apparent on bottles that were made prior to air venting in the mold. When molten glass is blown into a primitive non vented mold, there’s nowhere for the air to completely escape, some manages to escape through the top while some of it gets trapped between the glass and the mold surface, causing a whittly, wrinkle type appearance as seen below when looking through the large cobalt bottle. This big beauty is so whittled it gives a neat and lined up window display a ‘funhouse’ appearance. We bottle collectors like our ‘whittle.’ The gloppier, the cruder, the better.

Bottle makers in America realized this problem as early as the 1860’s, and some pin hole sized “pimples” are commonly seen on early American mold blown bottles that although feature these strategically placed pin sized vents, also feature a much smoother and better overall appearance. The tiny vent holes appear as raised pimples due to the molten glass emerging after the air has vented.

English glasshouses were not completely behind America in the evolution of bottle manufacturing; the appearance of which is likely due to obscure English glasshouses distant from those glasshouses in cities that were more influenced by the Industrial Revolution and the technologies that came with it. This beautiful and very large blue poison or essence bottle was either made in an industrious area of England in the 1870’s to 1880’s, or, it could be from a primitive, obscure country glasshouse and actually date to 1890-1910. Either way, it’s a fantastic, crude, and beautiful bottle and my twenty year old mystery is solved on it’s type and place of origin.

Thanks for the books John.