Much of the history we teach was made by people we taught.

-West Point History Department (unofficial motto)

Like stars in the famous play that became our history, the United States Military Academy at West Point produced a cast of leading actors during the early 19th Century like no other: Commander of the Confederate Army Robert E. Lee, second in the Class of 1829, Union General George Meade, Class of 1835, Confederate General James Longstreet, Class of 1842, and Commander of the Union Army and 18th President, Ulysses S. Grant, Class of 1843.

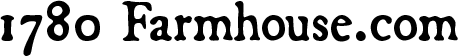

In 1846, a new set of famous leading men would also take to the stage to play both supporting and leading roles. Of all West Point classes, this was like no other. Literally in a class by itself, the Class of 1846 was the largest in West Point’s history at that time and historically the most famous. In 1842, one hundred and twenty-two cadets were accepted. In 1846, fifty-nine graduated. From this class came twenty-two Civil War Generals; twelve Union and ten Confederate. Commander of the Army of the Potomac George B. McClellan, Confederate General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, and Confederate General George E. Pickett are the top three household names of the West Point Class of 1846.

The most prominent Class of 1846 generals who made history during the Civil War.

In October of 1846, just three months after graduation, 53 of the 59 class members found themselves ordered to the very southernmost tip of Texas. In what was then known as Point Isabel, (now called Port Isabel) General Zachary Taylor and his men were encamped. Having just begun, the Mexican War loomed large. After victory there came the Indian Wars. But it was the soul testing Civil War, in which, unbeknownst to them at that time, these classmates would take up arms and fight each other. From the first shots fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, they would endure the bloody battles and heartbreak for four long years, until their poignant reunion on the courthouse steps at Appomattox.

Two Very Different Generals From the Class of 1846

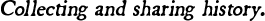

Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson

A very young Thomas Jackson, late 1840’s, after the Mexican War.

Thomas J. Jackson, from Jackson’s Mill, Virginia, came to West Point after his friend was accepted, got cold feet, and turned around and left upon arrival. Facing an uphill battle at West Point, he was known to burn coal into the late night hours, trading sleep for study. His entrance tests placed him at the bottom of the class, yet he doggedly climbed rank and graduated 17th; it was said by classmates that, given another year, he would have been first in the class. Jackson was stoic and undaunted, even as a young cadet. His drawing lessons gave him much difficulty and he had his own idiosyncrasies; he was known to keep his body in as straight a position as possible, fearing any bending or unnatural position could cause harm to his internal organs. His posture seemed ungainly; cadets were uncomfortable to look at him on a horse. But none of these quirks would matter. Jackson would go on to be commended for his bravery and brilliance with artillery in the Mexican War, after which, he taught at Virginia Military Institute until the secession and Civil War.

It was during a movement of Union forces towards the Confederate position on Henry House Hill at Manassas in July, 1861 that he acquired his famous nickname ‘Stonewall.’ Jackson’s mindset was to stand his ground and resort to bayonets if needed. Confederate General Barnard Elliott Bee Jr, before being killed moments later, is reported to have observed, “There stands Jackson, like a stone wall.” It remains unclear in what tone or inflection that statement was made. It’s possible General Bee, pinned down by heavy fire, was disgusted with Jackson not seeming to move froward to his aid, or, it may have been said in complete admiration as to Jackson seeming impenetrable and holding his ground. Nonetheless, the name struck a chord, not only with the South, but the North as well, and henceforth Tom Jackson was ‘Stonewall’ and his Brigade, the ‘Stonewall Brigade.’

April of 1863. The last photograph taken of Confederate General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson at Chancellorsville two weeks before he died.

Stonewall was Robert E. Lee’s right hand man, and commanded the Shenandoah Valley District, where he played the Union Army like a chessmaster. He would show up very surprisingly where the Union forces would least want or expect him to be. Even the Stonewall Brigade themselves marched relentlessly knowing, “no more than the buttons on their coats” where they were going. Jackson was very keen to fast pace his brigade to far apart areas to keep different commands of Union armies from joining together, a talent for which he was very successful. Through his intuition of knowing what the Union forces were going to do next, his ability to flank and rear the opposing armies was unparalleled.

Then a most tragic event occurred; on the night of May 2nd, 1863, Jackson was mortally wounded by skittish Confederate pickets at Chancellorsville and having survived the loss of his left arm, died a week later of pneumonia. Having struggled with his lessons at West Point, Stonewall Jackson proved himself a military genius during the Civil War and, many historians conclude, one of the best generals ever.

George ‘Little Mac’ McClellan

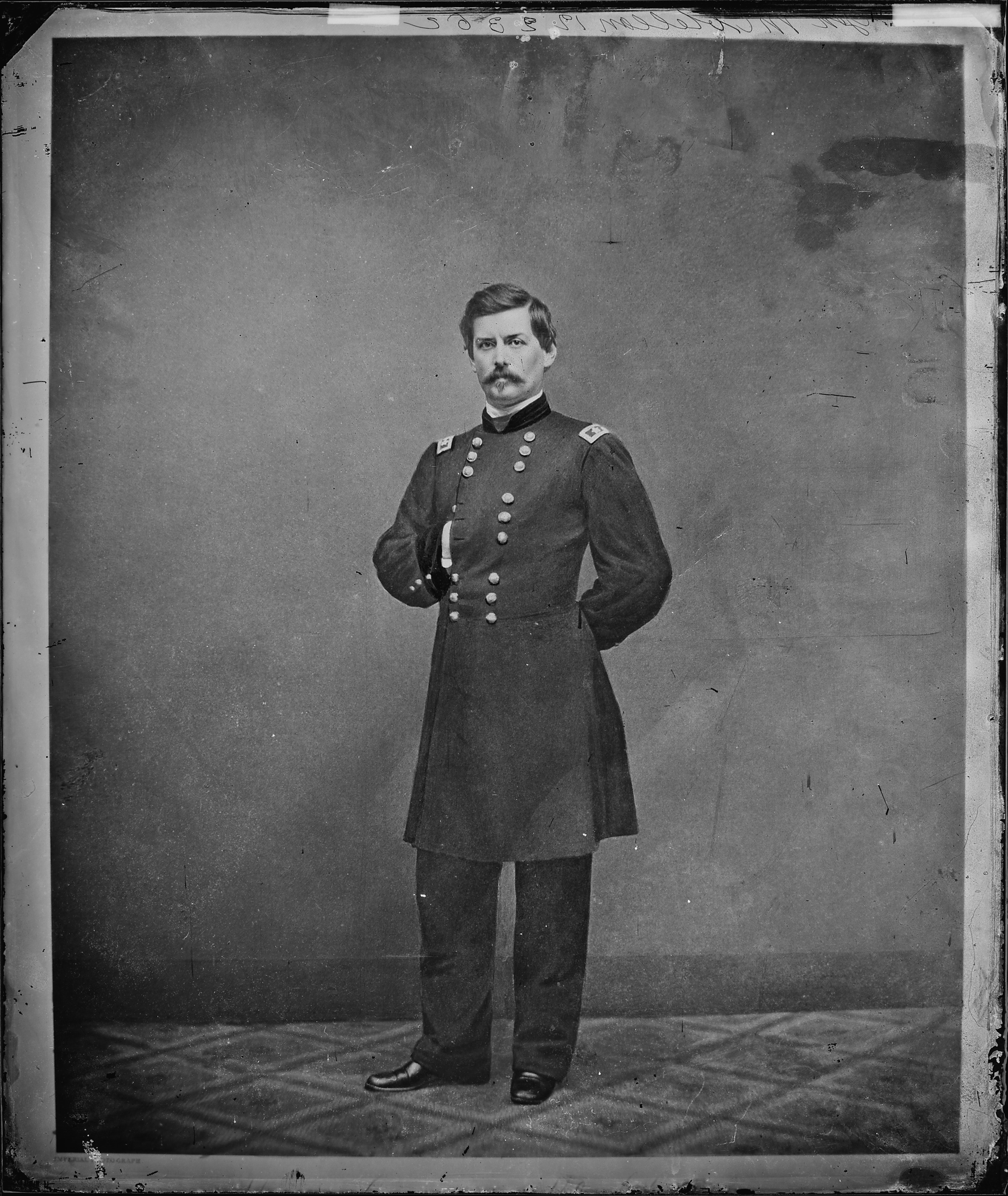

General George Brinton McClellan, Commander of the Army of the Potomac in 1862.

Born in Philadelphia in 1826, George Brinton McClellan was the son of a very prominent surgeon, Dr. George McClellan and a very socially active mother, Elizabeth Sophia Steinmetz Brinton McClellan. At age 13, he began studying Law at the University of Pennsylvania. Two years later, in 1842, disillusioned by the thought of becoming an attorney, he was accepted at West Point at a youthful age of fifteen years and seven months. From there, George B. McClellan would rise, but only so far. Unlike Stonewall Jackson, McClellan didn’t have to struggle through his studies, but he would have a problem with things like decision making and strategy.

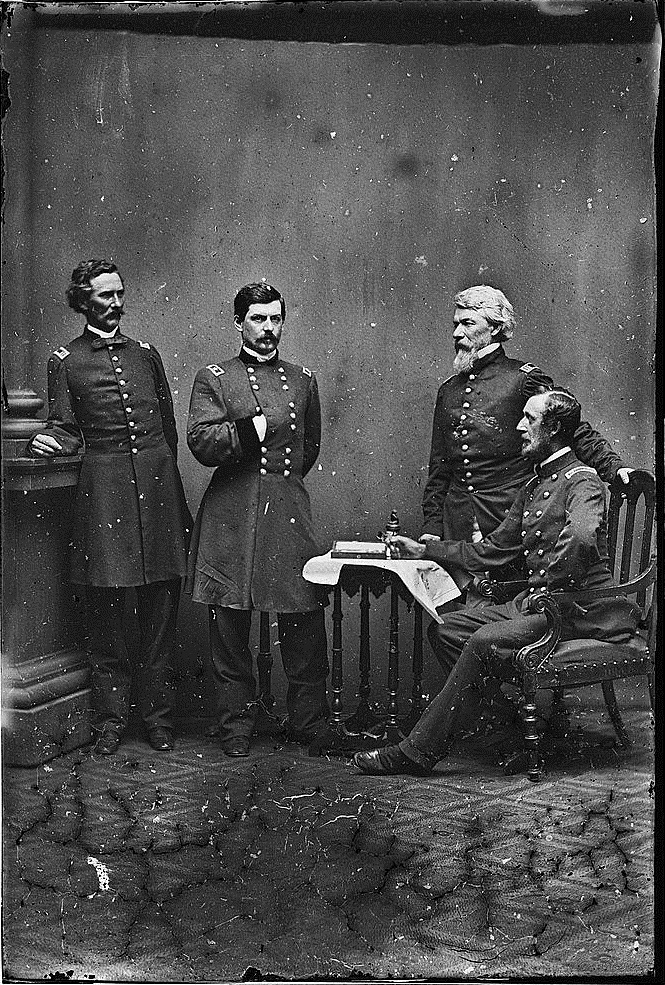

From the same photo session in 1862, George B. McClellan poses with his staff.

By 1862, he was the leader of the Army of the Potomac. That same year, the battle of Antietam ended his military career. McClellan’s hesitancy and over cautiousness-this time in particular his decision (or failure to consider even making a decision) to not send in his reserves when the Confederates lost their center and retreated-could have possibly shortened the war. Lee’s army retreated, but “Little Mac” chose not to pursue. By then President Lincoln had had enough of McClellan’s inaction and insubordination and relieved him of command on November 5th, 1862. He was replaced by General Ambrose Burnside (West Point Class of 1847.) McClellan’s failure to follow through at the battle of Antietam was the last of many straws which had tested President Lincoln’s patience. An earlier letter shows the predicament Lincoln always found himself in with McClellan:

My Dear McClellan:

If you are not using the army, I should like to borrow it for a short while.

Yours Respectfully,

Abraham Lincoln

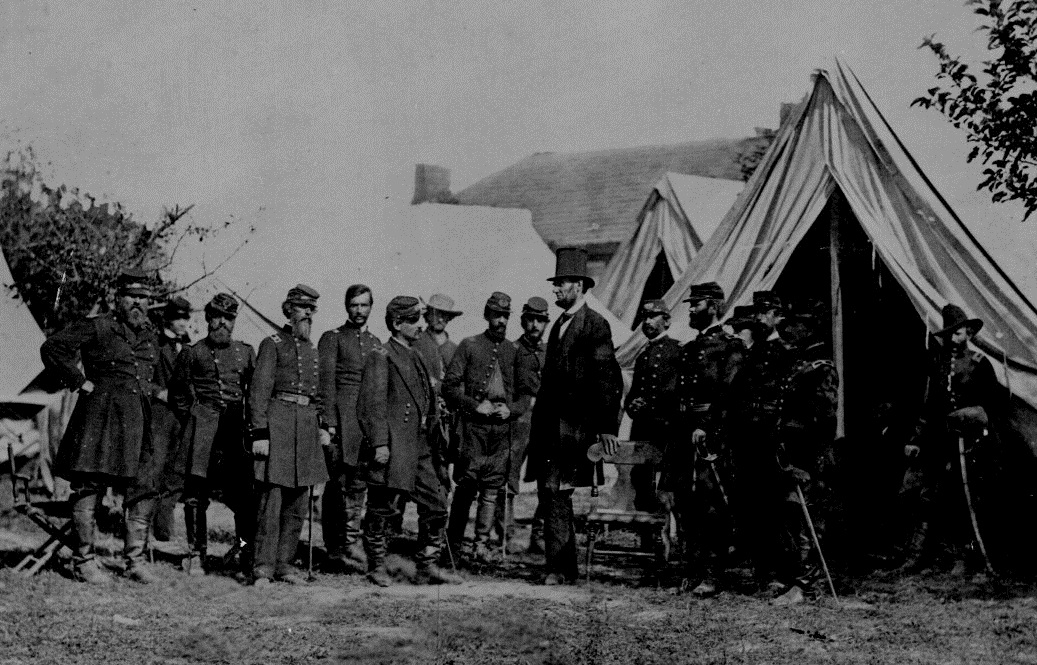

McClellan and his staff with Lincoln at Antietam, October 3rd, 1862. McClellan’s posture before the President alludes to the strained relations which would cause Lincoln to fire and replace him with Ambrose Burnside. Off on the far right is none other than George Armstrong Custer, graduate of the West Point Class of 1861. Custer, like George E. Pickett both graduated last in their classes due to demerits.

October 3rd, 1862. McClellan’s tent after the battle of Antietam. Lincoln pays a visit to discuss events and McClellan does not appear pleased. One month later, he would be relieved of his command. The expert coloration of the photo really brings it to life.

McClellan’s posed portraits have him appearing seemingly smooth and steadfast, capable, and agressively polished. In reality, his personality was as smooth as sandpaper. Of course, McClellan had his good points; he was a very talented organizer and trainer of soldiers. It was as a strategist and decider that he fell short. He did have the safety of his men at heart, which they knew, but there is also little doubt that he was very self absorbed. It was once said of him that, “he was the only person who could strut while sitting down.” In letters to his wife Mary Ellen, he often referred to Lincoln as a “Gorilla.”

Perhaps aside from his utter disrespect for Lincoln, there was one other thing for which McClellan was successful at, his courtship and marriage of Mary Ellen Darcy. His roomate at West Point, Ambrose Powell Hill was less so. A.P. Hill had courted Mary as well and even proposed. The Darcy family did not approve of Hill and he withdrew his proposal. A member of the Class of 1846, Hill was left back to graduate in 1847 due to contracting gonorrhea in the summer of 1844.

After the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant was asked his opinion of McClellan as a General. He said, “McClellan is to me one of the mysteries of the war.” McClellan lost his run for President against Lincoln in 1864, but went on to become the Governor of New Jersey. He died in 1885.

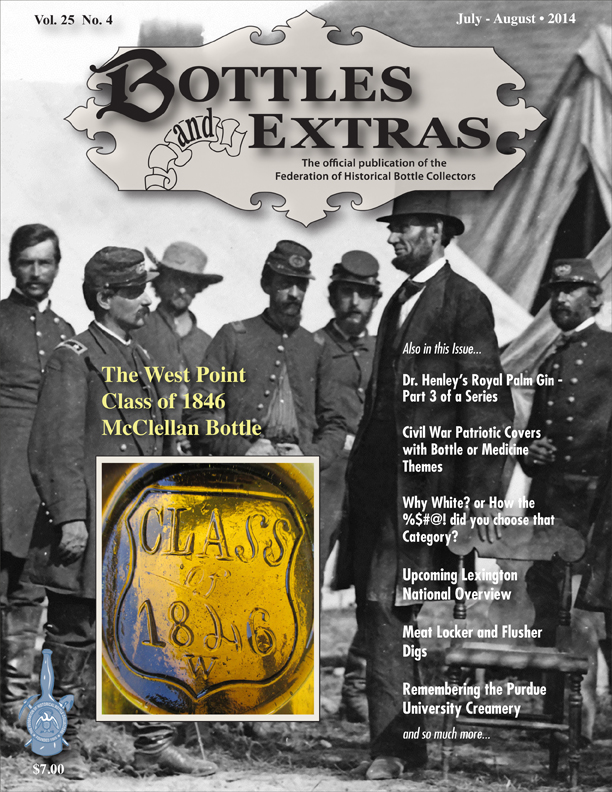

With such a historic class, a most famous cast of leading actors, you’d be disappointed if someone didn’t have a bottle made to commemorate the West Point Class of 1846.

But someone did.

A most interesting and extremely rare whiskey bottle, mouth blown into a mold with a very distinctive applied seal. Since time out of mind, this bottle was thought by the historic bottle and glass community to be a Harvard class bottle.

A detail photo of the applied seal. Note the Federal Shield and the letter W.

The iron pontilled base which is mold embossed, DYOTTVILLE GLASS WORKS PHILA.

A very serene illustrated scene. Looking west at Dyottville Glass Works in 1831.

The bottles were commissioned at Dyottville Glass Works in Philadelphia in the late spring of 1846. Graduation was June 12th. The wealthy and socially prominent McClellan family lived on Spruce Street in Philadelphia. George B. McClellan had graduated second in his class. There was every reason to have a party. One could easily imagine George’s father riding his carraige over sunny cobblestone streets to Dyottville, by the Delaware River, to order the bottles for his son’s graduation party. The reason he asked for an applied seal on the bottles rather than embossing had everything to do with practicality. Having a mold made would take time, whereas having the bottles made with an applied seal could be easily done as quickly as making the bottles themselves. Most importantly, he must have surmised, it made little sense having an expensive mold made for just a one time production.

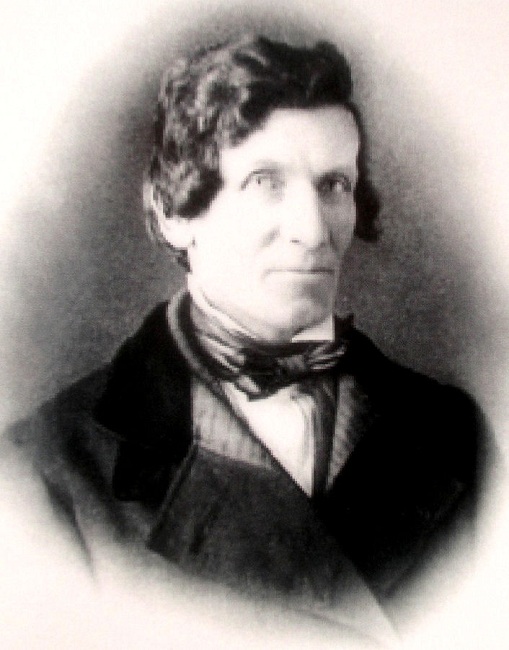

It was unfortunate that Dr. George McClellan died only a year later, in May of 1847, due to a perforation in his small intestine. He was a brilliant surgeon who not only founded the Jefferson Medical College, he was the first to advocate teaching medical students by having them observe experienced doctors treating patients.

Dr. George McClellan, father of George Brinton McClellan.

Having networked far and wide in my attempt to acquire an accurate number of these bottles in existence, as of this writing, there are only seven. It’s still unknown how many were made. It is improbable that all 59 class members attended the party. A McClellan family party with classmates who were able to attend, relatives, and close friends and Philadelphia Society seems most likely, and would put the number even lower.

While researching this bottle for almost two years, I’ve been nibbling on parsimony while shaving with Occam’s Razor; it was some time after knowing what the bottle is not that caused me to lift my eye from the proverbial microscope and see the whole picture. There simply was no other class than West Point, not in 1846-not in the entire 19th Century. It’s not a Harvard, Yale, or Princeton bottle. Nor is it from any dinner club. It’s not from any of the standard ‘W’ named colleges. Having traveled down these many roads; all proved exhaustive dead ends. The embossed W and the federal shield are key. How fascinating, that my research led me to learn that in 1835, it was none other than West Point that started the class ring tradition.

Class ring, West Point 1841.

Prior to the early 1900’s, the cadets designed their own rings. It’s most telling to compare a West Point ring from 1841 (above) to the logo in the seal on the 1846 bottle. On the ring not only is the federal shield prominent, but the W (without a P) is clearly visible despite the missing corner fragment. This compelling evidence shouts loud and clear the provenance of this bottle. In the 1840’s, this combination of the federal shield and the W alluded to West Point and no other institution.

The federal shield is also very prominent on grave stones at West Point Cemetery and also on General George Armstrong Custer’s marker where he made his last stand at the Battle of Little Bighorn. He was last in his class in the West Point Class of 1861 and his remains are interred at West Point Cemetery.

Looking back at the Mexican American War, especially the Port Isabel location where the class was first ordered in 1846, there is a surprising connection. Even if just a coincidence, it’s a concrete one. In that very southernmost tip of Texas, an example turned up in the late 1980’s. A glass collector, now deceased, sold an example to an owner of one of the most prominent collections of Mexican American War artifacts. The bottle was sold as a West Point bottle and is currently displayed as a centerpiece in that collection in the Port Isabel Museum.

The Port Isabel example, having been cleaned and ready for display as the centerpiece in the Mexican War Collection in the Port Isabel Museum.

The museum, interestingly enough, stands on the grounds where General Zachary Taylor and his men had camped in 1846. (Did a class member who attended the party bring his along only for it to survive intact and stay in the area?) This collector informed me that he had read a few books, including an obscure cadet memoir some twenty years ago in which was stated that: “the father of one of the cadets supplied liquor for the graduation party which they called Fandango.” How utterly fascinating. The cadet memoir remains elusive to the collector’s memory after some twenty years and I’m still on the lookout for it. With absolute certainty, I believe West Point itself had nothing to do with the commissioning of these bottles.

The term Fandango (the name for a Spanish dance dating back to the 17th Century) clearly coincides with the fact that the class members knew they were going to Mexico after graduation. There was only one class member who would have coined this term for the party: George Horatio Derby, who graduated 7th in the class and was (my favorite class member) also known for his hilarious antics. His terms and phrases are known as ‘Derbyisms.’ The term ‘Fandango’ to name a graduation party held before fighting the Mexican War is a classic Derbyism.

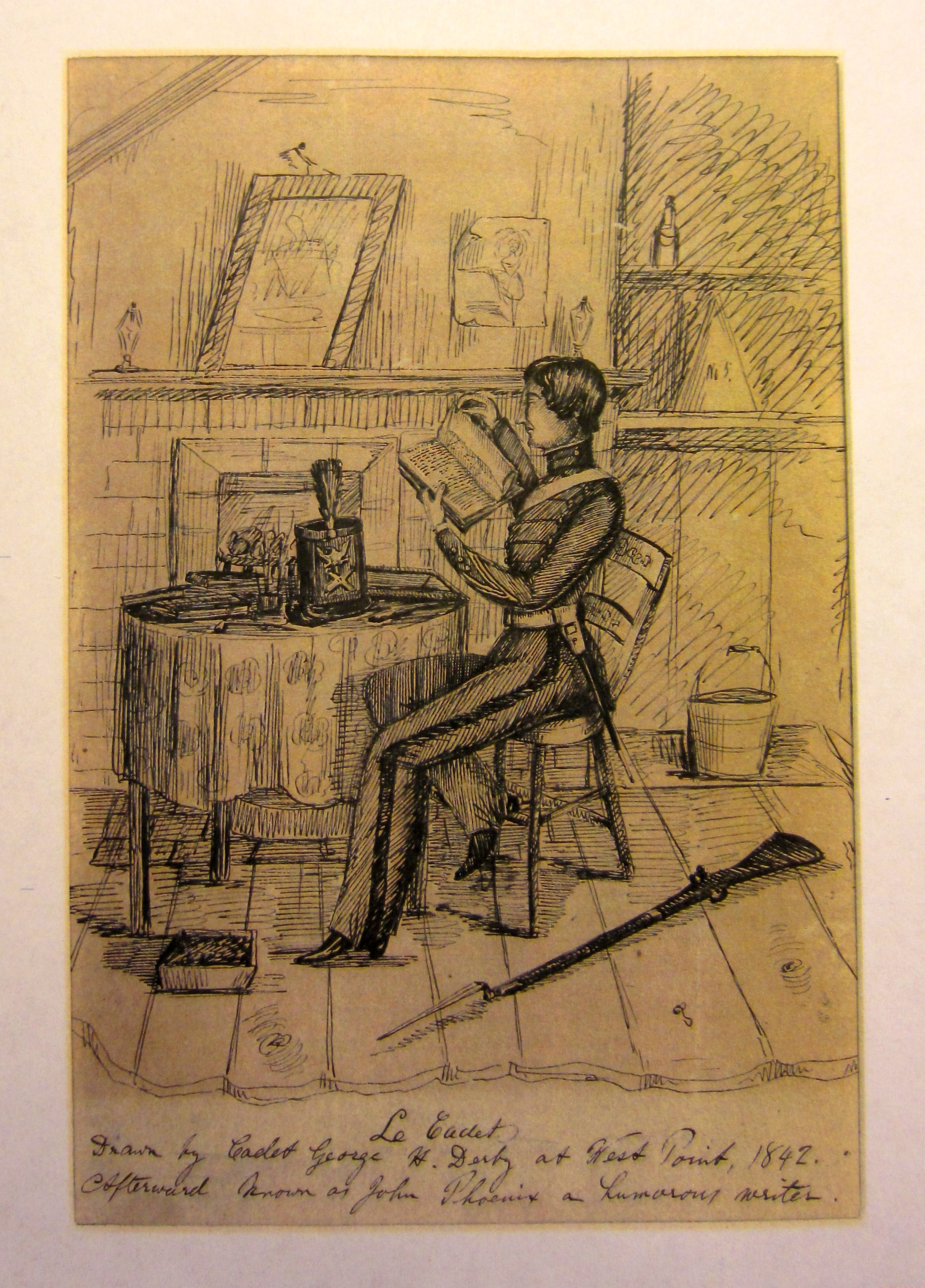

George Horatio Derby in 1846. Class prankster, he went on to become a brilliant engineer and humorous writer. He died in 1861 at age 38.

Derby played the role of prankster with such tact and pure genius that he never got in any trouble. His offenses could not be categorized. He drew monsters in his geology textbook which was then indignantly confiscated and given to the academy board members, who, while looking at it, laughed themselves silly behind a closed door. When asked to come forth to the blackboard and draw a pump, the pump would somehow take on characteristics of the professor. He was legendary and went on to become a brilliant engineer and humorous writer, going by the nom de plume John Phoenix.

Also an incredible draftsman, in 1842, George Derby penned a drawing of a West Point Cadet in his room. Depicting a cadet studying, many items are in disarray, (a rifle laying on the floor for one.) Any cadet would have received multiple demerits for such offenses. This satirical drawing at first seemed to be quite a clue in the bottle research as there is a cylindrical type bottle on a shelf with lines suggesting a seal on it. With absolute certainty it’s really an ink bottle with the suggestion of a label as the drawing was done in 1842 when there were still 122 cadets. Not only that, West Point would have never allowed whiskey bottles on the premises. Or, perhaps it is a whiskey bottle-part of Derby’s joke.

Without a doubt, these bottles were made the same day from the same batch of glass. In March of 2013, a collector friend and I brought our examples together for a first time ‘Class Reunion’ at the Baltimore Bottle Show. These extremely rare historical glass artifacts had not been next to each other in 167 years. Astounding that these fragile glass bottles have withstood all those years to serve as a reminder of the greatest class ever.

Holding in my hand possibly the most historical bottle ever; a souvenir from the 1846 summer Fandango?

After 167 years, I finally got my invitation.

My hat is off to The Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors for publishing this in their July/August 2014 issue of their official publication Bottles & Extras. My special thanks to the FOHBC President, Ferdinand Meyers V, for all his inspiration and dedication to the historical glass collecting hobby.

Resources:

Waugh, John C. The Class of 1846 From West Point to Appomattox: Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan and their Brothers 1994 Random House ISBN 0-345-43403-X

The United States Military Academy Archives and Library and the George H. Derby Papers

Library of Congress George Brinton McClellan Papers